In the face of punishing international sanctions and a growing consensus that hard-line policies are no longer paying off, Iranian voters last month elected a president committed to easing tensions with the international community and digging their economy out of a deepening hole. In the West, the main question is whether he will make the concessions needed to reach a deal over his country’s nuclear program.

It’s unclear what Hassan Rouhani can achieve in the short term on the nuclear issue, which is largely controlled by Iran’s supreme leader, not its elected president. Progress on that issue, though, is far from the only test of Mr. Rouhani’s commitment to change.

Many Iranians wondering what the Rouhani presidency can really bring to reflect statements made during his campaign, which departed sharply from the radical sloganeering against personal liberties that marked the last eight years. In the run-up to the election and since his victory, Mr. Rouhani has repeatedly referred to freedom and liberty, including the need to free political prisoners, the importance of national reconciliation, and the “de-securitization” of public space. After his victory, thousands of Iranians took to the streets to celebrate. YouTube videos that circulated showed crowds in various cities chanting pro-democracy slogans and demanding greater freedom. The security forces, remarkably, stood on the sidelines.

Of course, with the candidates pre-approved and the pre-election environment highly restricted, the election was neither free nor fair. Mr. Rouhani’s past does not suggest that he will undertake major reforms. He is a moderate cleric and regime insider. He held high-ranking office at the Supreme National Security Council during the harsh crackdown against student protests in 1999, and was publicly silent when security forces responded brutally to the 2009 post-election protests.

Yet Mr. Rouhani’s calculated and nuanced references to personal freedoms suggests he is sensitive to the long, dark shadow cast by the disputed 2009 presidential elections. Despite many legal and political barriers, what Mr. Rouhani does and says on human rights matters. This will be particularly important when it comes time for him to get the supreme leader’s sign-off on members of his Cabinet, who will play a decisive role in restricting — or respecting — the rights of the Iranian people.

If Mr. Rouhani is sincerely committed to — and capable of — pursuing reform, here are some initial steps he could take, once inaugurated, to demonstrate this commitment and capability. All would require a degree of political courage and skill, but should be achievable within the circumscribed mandate of the president of Iran.

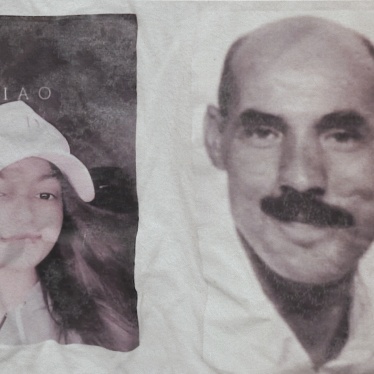

Free political prisoners: “Political prisoners should be freed” was a common chant at pre- and post-election rallies this year. Although security and judicial affairs generally fall outside the president’s control, Mr. Rouhani can and should call for fair trials and champion the right of prisoners not to be tortured or otherwise mistreated. A key test will be how he handles the ongoing detention of opposition leaders Mehdi Karroubi, and Mir Hossein Mousavi and his wife, Zahra Rahnavard, who have been under house arrest for nearly two-and-a-half years without charge — in clear violation of Iranian law.

While he may have less room to maneuver vis-a-vis convicted opposition members, Mr. Rouhani can also call on the authorities to release other political prisoners, including lawyers, rights activists and members of Iran’s targeted religious minorities like the Bahais.

Respect media freedoms: On June 29, a tweet allegedly linked to Mr. Rouhani’s personal account read: “The system that takes its legitimacy from [the people should] not [be] afraid of [a] free media.” Earlier, in response to questions during his campaign, Mr. Rouhani said he would allow the reopening of the Iranian Journalists Association, which was shut down in 2009. He should also make it a priority to review and push for the release of some 40 journalists and bloggers who are in prison on speech-related charges.

Expand academic freedom: Mr. Rouhani should press for decreased influence of security forces, such as the volunteer Basij militia, in Iran’s universities. As a first move, he could appoint a more progressive science and technology minister dedicated to protecting academic freedom. He should also push to remove the disciplinary boards that monitor the peaceful political and other activities of students, reinstate students expelled due to their activism and roll back regressive gender separation and exclusion policies that effectively ban men and women from studying some subjects.

Unshackle independent organizations: Former President Mohammad Khatami, who endorsed Mr. Rouhani, made support for civil society a centerpiece of his reformist agenda during his term from 1997 to 2005, only to be reversed by President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad. Mr. Rouhani should lift restrictions on the independence and activities of nongovernmental and trade groups such as the Iranian Bar Association, the House of Cinema (the country’s largest independent film society), and labor unions and syndicates.

If Mr. Rouhani moves to make these changes — even if progress on the nuclear issue remains slow — we will know his talk of change was intended to produce results. The converse is also true. The international community, hoping for change abroad, should take its cues from how Mr. Rouhani upholds his promise for reform at home. His Cabinet appointments may give the first clue of what is to come.

Sarah Margon is the acting Washington director and Faraz Sanei is a Middle East researcher focusing on Iran at Human Rights Watch.