“Maria,” a Ugandan worker, paid $400 in 2013 to an agency in the United Arab Emirates that promised her a job in a mall in Dubai. Instead, the agency placed her as a domestic worker with half the salary she had been promised. Maria told me that her employer took her passport and phone, made her work from 5 a.m. to the middle of the night with no day off, beat her, kept her hungry, and paid only a fraction of the wages she was owed. When she finally fled, she said, the Ugandan embassy assisted her on her visits to the immigration department, but did not offer her safe shelter.

On December 18, International Migrants Day, all governments, including Uganda, Kenya, and Ethiopia should commit to better protection for the growing numbers of migrants like Maria that face abuse in the Middle East.

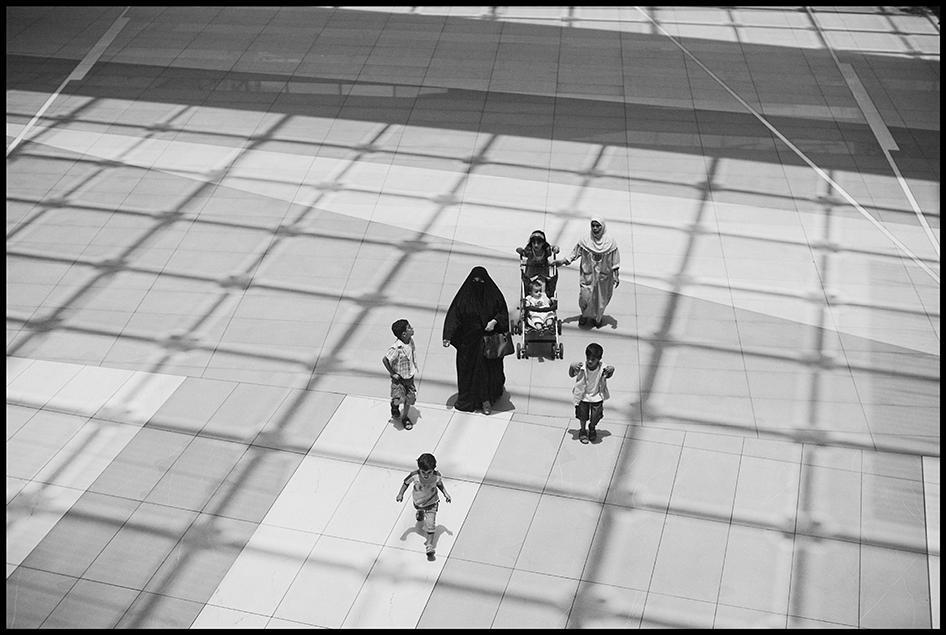

Maria was among 99 women I interviewed in late 2013 for the Human Rights Watch report “I Already Bought You: Abuse and exploitation of female migrant domestic workers in the United Arab Emirates,” issued in October 2014. At the time, countries like Uganda and Kenya were relatively new to sending domestic workers to the Middle East, which had typically recruited from India, Indonesia, Ethiopia, the Philippines, and Sri Lanka.

Unfortunately, but unsurprisingly, media reports of abuse of Kenyan and Ugandan domestic workers have increased. Like their counterparts from Asia, their woes include unpaid wages, long working hours with little or no rest, confinement to the household, passport confiscation, inadequate food, poor living conditions, and physical and sexual abuse.

It is no mystery why the estimated 2.4 million domestic workers in the Gulf often face abuse. While some employers treat them well, major gaps in labor laws in the gulf countries coupled with unethical recruitment in home countries foster exploitation and violence. Under the visa sponsorship, or kafala, system, domestic workers cannot transfer employers before the end of their contracts without their employer’s consent.

Both Uganda and Kenya have experimented with banning migration of domestic workers to the Middle East. But previous experience shows that when labor-sending countries try to protect their citizens through bans on migrating, unscrupulous recruiters instead route migrants desperate for jobs through unregulated channels. Or they turn to other countries with fewer protections. In fact, they turned to Kenya and Uganda when some other countries barred their workers from going. Saudi Arabia has reportedly recently started recruiting from Somalia.

Governments in East Africa should learn from other labor-sending countries that have spent years dealing with cases of abused workers. The most promising practices include strong and consistent monitoring of recruitment agencies, bilateral diplomatic efforts at the highest political levels, ensuring that domestic workers know their rights and where to get help, and expanding the staff and resources of embassies to provide emergency shelter and to address legal and social protection for migrant workers.

In October, a Kenyan Foreign Affairs Ministry official told me that they are proposing labor attaches for consulates, working on an exit visa system for domestic workers, and seeking to increase punishments for malpractice by recruitment agencies. Last week, the National Assembly committee on Labour and Social Welfare called for “a special fund to the missions in the Middle East, especially the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia…including setting up a safe house.” It is important for these proposals to turn into concrete actions.

Uganda has also initiated some changes. In July, the government signed a memorandum with Saudi Arabia to entitle domestic workers to an eight-hour working day, a return air ticket, decent accommodation, identity cards on arrival, health insurance and a monthly minimum wage of 750 Saudi Riyals (around 710,000 Ugandan shillings or US$200). The government is reportedly seeking similar agreements with Qatar, United Arab Emirates, Bahrain and Kuwait.

But often these bilateral agreements are weak and difficult to enforce if there are poor national protections. They will do little to safeguard migrant domestic workers, however good the stated conditions. As such, labor-sending countries should also press the gulf countries to reform the kafala system to allow migrant workers to change employers, and to bring their labor laws in line with the International Labour Organisation’s Domestic Workers Convention. They should avoid unhealthy competition with other labor-sending countries and work together to demand a set of minimum standards, including a minimum wage, for all migrant domestic workers.

Kenya and Uganda are at a turning point. They know that many of their citizens seek to improve their fortunes abroad, but they have not set up basic safeguards to protect them. Instead of repeating the cycle in other countries, that have been shocked by egregious cases of abuse of domestic workers, they should act decisively now.

Maria, like tens of thousands of women, seized what she thought was an economic opportunity. But without real reforms in the Middle East, and better protections from her own government, there will be many more Marias who are deceived, abused, and denied justice.