“On top of the danger and anxiety facing civilians fleeing ISIS control, some are now being detained and denied contact with their families by Iraqi and KRG authorities,” said

Lama Fakih, deputy Middle East director. “When detainees are held without contact with the outside world, in unknown locations, that significantly increases the risk of other violations, including ill-treatment and torture.”

Iraqi and KRG authorities should make efforts to inform family members, either directly or indirectly, including through camp management officials, about the location of all detainees. The authorities should make public the number of fighters and civilians detained, including at checkpoints, screening sites, and camps during the conflict with ISIS, and the legal basis for their detention, including the charges against them. Iraqi and KRG authorities should ensure prompt independent judicial review of detention and allow detainees to have access to lawyers and medical care and to communicate with their families.

On October 17, 2016, the Iraqi central government and KRG authorities, with the support of an international coalition,

announced the start of military operations to retake Mosul, Iraq’s second largest city, which ISIS captured in June 2014. Anti-ISIS forces also encircled the city of Hawija, 57 kilometers west of Kirkuk and 120 kilometers southeast of Mosul, which ISIS also captured in June 2014, and began operations to retake the city. Since the operations began,

at least 41,900 people have fled into northern Syria, the Kurdistan Region of Iraq (KRI), and elsewhere in Iraq.

The people Human Rights Watch interviewed individually and in groups had recently escaped from ISIS-held areas near Mosul and Hawija. The interviews were conducted in the Jadah camp for displaced persons, 65 kilometers south of Mosul and under the control of Iraqi Security Forces, and the Zelikan camp, 43 kilometers northeast of Mosul and under the control of the KRG’s security forces.

Those interviewed in both camps consistently said that detainees held by both Iraqi and KRG forces had not been able to contact them and that in many cases they did not know where the detainees were being held. Even in one instance in which family members knew that their loved ones were being held in the building where they had been screened, the detainees had been denied the right to communicate with the family members and with a lawyer, relatives said.

On October 27,

Human Rights Watch issued a report on the screening procedure facing displaced men and boys from ISIS-held territory at Debaga screening center and camp, in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq. It found that KRG forces have detained men and boys ages 15 and over for indefinite periods stretching from weeks to months, even after they pass an initial security check for possible ties to ISIS. While being screened, detainees told Human Rights Watch, they are denied access to lawyers and detained even in the absence of evidence that they are not individually suspected of a crime.

In a follow-up visit to Debaga camp on October 28, four families told Human Rights Watch that after KRG security forces detained seven male family members at checkpoints and in the screening area at the camp, none of the families were able to get answers from KRG security forces at the camp about where their relatives were being held. The men had been held for up to 11 days, they said.

Enforced disappearances, which occur when security forces detain and then conceal the fate or whereabouts of a detainee, placing them outside the protection of the law, are violations of international human rights law and can be international crimes. Depriving detainees of any contact with the outside world and refusing to give family members any information about their fate or whereabouts can qualify their detentions as enforced disappearances.

Dr. Dindar Zebari, chairperson of the KRG’s High Committee to Evaluate and Respond to International Reports, provided Human Rights Watch with

an explanation of KRG security force screening and detention processes for displaced persons. In it, he stated that KRG authorities are committed to informing the families of detainees of the process and status but, “due to a lack of personnel and financial resources this task may at times be a difficult one.”

“Iraqi and KRG authorities should take steps to make sure that their efforts to keep civilians safe from ISIS attacks don’t undermine basic rights,” Fakih said.

Jadah camp

Four men from the subdistrict of al-Shura, 40 kilometers southeast of Mosul, separately told Human Rights Watch that on October 29, when Iraqi federal police took control of the area, they detained two men suspected of being affiliated with ISIS and took them away. The four witnesses are now at Jadah camp in adjacent tents and are in close contact with the two detained men’s family members, who are also in the camp. The four men said that the relatives of the detained men do not know where they are being held and that the detainees have not phoned them, but that the families are afraid to ask security forces where the men have been taken. Other interviewees raised the same concern.

The four men from al-Shura said that before they were allowed to go to the Jadah camp, federal police took them and the remaining men and boys 15 and over from the village to a screening center run by the National Security Service (NSS) in a mosque in the town of Qayyarah, six kilometers north of the camp.

There, the NSS officers searched and interrogated them, checked their identity cards, and confiscated their sim cards. The interviewees said that they, and the men and boys they were held with, were in the screening center for a few hours before the NSS allowed them and most of the other men to move to the Jadah camp and reunite with their families. But some men were moved to an unknown location, the four men said.

They said that the NSS took at least three men from their group from the mosque and moved them to an unknown location. Four relatives of the three men said on October 31 that they still had no idea where their family members were being held and had not heard from them. They said that they had not yet asked the authorities about the men’s whereabouts because they had full faith that the authorities would release those without ISIS-affiliation promptly to the camp.

Five policemen at Jadah camp from Hammam al-Alil, 30 kilometers southeast of Mosul, said that the NSS also took two policemen who arrived with them at the camp on October 29 from the camp. They did not know where they had been taken and had not seen them again. These men all fled ISIS-controlled territory together, without their families, but live in adjacent tents at Jadah camp and described themselves as close friends. They believed that if the detainees were able to contact anyone from detention, the men in the camp would have heard from them. They also said that they had not yet asked the authorities about their whereabouts because they believed that the authorities would realize that these men, who had both been detained and abused by ISIS over the past two years, were innocent and release them promptly to the camp.

An international journalist who visited the Jadah camp on October 26 at around 4 p.m. told Human Rights Watch

she witnessed eight men kneeling on the ground outside a tent with NSS officers with laptops inside. They were blindfolded, with their hands tied behind their backs and one officer was standing above them tapping a thin black stick on their heads. Two other officers were sitting in plastic chairs looking at the group. Camp management staff told Human Rights Watch that the NSS were taking men who were possible ISIS-affiliates away from the camp but did not know where they were being taken.

Zelikan camp

On November 7, Human Rights Watch visited Zelikan camp, 29 kilometers northeast of Mosul, and spoke to 18 people, including family members of seven men who were detained and five who had been released. They said that they and about 200 other families had fled the village of Abu Jerbua, as ISIS retreated on November 1.

Afterward, they said, KRG security forces took all the families to the Zelikan camp’s screening center, where they were held for two nights, before security forces transferred them to the main camp.

While at the screening center, the Asayish, which are KRG security forces, picked out 22 men from the group, holding 11 for two days and then releasing them and keeping the remaining 11 in detention, said 5 detainees who saw the men taken away. Those who had been released said that the Asayish forces took the remaining 11 men away from the screening center on November 3. Human Rights Watch visited the screening center on November 7 and found it empty.

Relatives of five of the men who were moved to an unknown location said that they have asked Asayish officers about where their relatives are and why they are being held but received no answer and have been unable to contact the men. An hour before Human Rights Watch visited the camp, Asayish forces arrested another villager from the group at the camp, his father said. He said he did not know where his son was taken or why. When he asked, an Asayish officer told him, “It’s none of your business.”

Dabaga camp

One woman from Hawija spoke to Human Rights Watch, surrounded by her family of five young daughters and a son:

A group of men in the Debaga screening center also told Human Rights Watch that they observed security forces running the site remove two or three men a day on average from the center, out of about 400 currently being held.

One man who arrived at Debaga with his wife was separated into the screening area on October 15, and taken to a prison in Erbil two days later. While in prison, he said, he did not have access to his wife or to a lawyer, and was held in a cell with about 35 to 40 other ISIS suspects. He was never interrogated, and was moved five days later back into the screening area. He did not understand why he had been cleared for prison release but was still being held and prevented from joining his wife.

Hasansham camp

On November 7, Human Rights Watch visited Hasansham camp, 30 kilometers east of Mosul. Researchers interviewed 11 Shabak villagers from the town of Gelyuhan, 5 kilometers southeast of Mosul, who said that on November 3, as ISIS retreated from the area, they and at least 150 families fled toward Ali Arash, 4.5 kilometers away, the first village along their route.

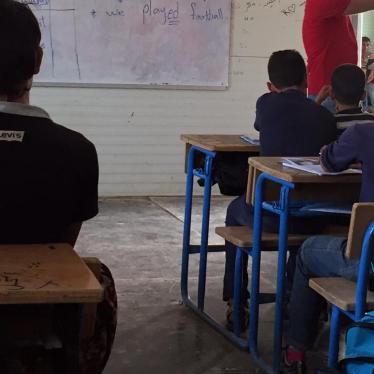

There, the interviewees said, the government-allied armed group known as the Hashd al-Sha’abi, a Popular Mobilization Force (PMF) made up of Shabak fighters, put the women, girls, and young boys in the second floor of a school, and the men and boys 15 years old and above downstairs in classrooms.

The fighters called out three men’s names and then took the men into a separate room. The next morning at 10 a.m., Iraqi military officers arrived and, nine of the men said, went into the classroom and said, “Why are you here? You are free to go!” At that point, on November 8, the families were allowed to leave and go to Hasansham camp, but the three men were kept in custody, according to all of the interviewees.

Human Rights Watch interviewed a villager arriving at the camp directly from the school on November 7, who said he had seen the three men still being held in a classroom at the school that morning. The mother and brother of one of the detained men said that a family friend in Baghdad who is linked to the Shabak forces said that her son was being held because he was accused of looting fighters’ homes, abandoned once ISIS came to the area. The families have had no contact with the three men still being held.

Iraqi forces, including PMF forces, and KRG authorities should not use schools for security or military purposes such as screening and detention centers except as a last resort when no other facilities are available, Human Rights Watch said. Such use of schools can delay the re-opening of the schools to teach and provide other services to children and lead to damage to classrooms and equipment.