This week, Rwanda has a routine session before the United Nations Committee Against Torture (CAT), a body of human rights experts that monitors implementation of the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (Convention against Torture). It will be an opportunity for these experts to question the government on its implementation of the treaty, which Rwanda ratified in 2008, and to examine allegations of non-compliance. The CAT will have plenty of work.

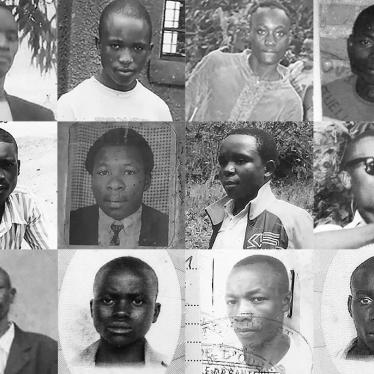

For at least the last seven years, Rwanda’s military has frequently detained and tortured people, beating them, asphyxiating them, using electric shocks and staging mock executions. In October, Human Rights Watch issued a report documenting these abuses in military camps around Kigali, the capital, and in the northwest. Most of the detainees we spoke with were held incommunicado, meaning without contact with family, friends, or legal counsel. Many were held for months on end. Most were civilians suspected of working with armed groups, although some were former fighters.

Detainees were tortured to extract confessions or accusations against others. One of the former detainees we interviewed, Ernest (not his real name), explained how military officials tortured him at Kami, a notorious camp outside Kigali. He said he was told to confess to belonging to the Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda (FDLR), an abusive armed group in neighboring Democratic Republic of Congo, some of whose members participated in the 1994 genocide in Rwanda. Ernest said that when he refused to confess, soldiers “brought a plastic bag and put it over my head and started to ask questions. After a few minutes, when they saw that I was suffocating, they stopped.” He said they suffocated him four more times until he defecated on himself. “I thought I was going to die,” Ernest told us.

In dozens of cases, former detainees said they told their torturers whatever they wanted to hear to stop the pain.

Some of the detainees were released after being held for weeks or months at the military camps, but many were transferred to civilian prisons and put on trial. Their forced confessions were used against them. When the accused described the torture and unlawful detention they had endured before being transferred to the civilian prisons, judges and prosecutors dismissed the allegations, even though they should have ordered investigations. The judge told one torture victim: “Do not come back to [the issue of] torture. You don’t have any evidence to prove it.” This was a common response to those who dared to speak up in court.

This documented torture violates Rwanda’s obligations under the convention, and the Rwandan government should be taking these allegations seriously. Instead, authorities have just brushed them off.

Despite the government’s ongoing and systematic use of torture, Rwanda ratified the Convention against Torture’s optional protocol, known as the OPCAT, in June 2015. The protocol requires countries to set up a system to prevent torture at the national level and to allow the Subcommittee on Prevention of Torture, a UN body, to visit detention sites. The Rwandan government has yet to create this mechanism, despite a deadline of within a year of ratification. But a visit from the Subcommittee caused equal concern. In late October, the members had to suspend their visit and leave sooner than planned, citing obstruction from the Rwandan government and fear of reprisals against people they interviewed. This was only the third time in 10 years that the Subcommittee has suspended a state visit.

The Rwandan government has refused Human Rights Watch access to military detention centers, jails and prisons for years. And, of even greater concern, we continue to document reprisals against those who dare to speak out about human rights abuses against them or their family members. Many former detainees told us that they were threatened not to talk about the torture they endured. If they did, they risked being sent back to the military camps. This is a common tactic in Rwanda with regard to sensitive human rights abuses. In the last few months people who spoke with us about extrajudicial killings in the west have been threatened or even detained and told they would “see what the government would do to them.”

The government has announced it is “consider[ing]… options in respect of the Optional Protocol,” which could include withdrawing from it altogether. But while the Subcommittee has not spoken publicly beyond issuing a news release, it was probably on to what so many Rwandans know but can’t say: the systematic use of torture is real and strikes fear into the hearts of many Rwandans.

The CAT should hold Rwanda accountable for use of torture and violations of the Convention against Torture. As the government continues to shun groups like Human Rights Watch or on-site investigations by bodies like the Subcommittee, the CAT may be the last hope to publicly address this scourge in Rwanda.