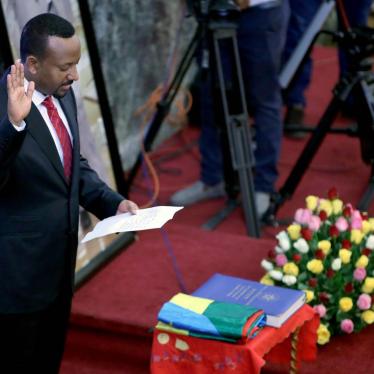

One year ago this month, Dr. Abiy Ahmed was sworn in as prime minister of Ethiopia. His first few months in office saw many positive human rights reforms and a renewed sense of optimism following several years of protests and instability, along with decades of repressive authoritarian rule. Thousands of political prisoners have been released, a peace agreement has been signed with neighboring Eritrea, and Abiy has pledged to reform repressive laws. But in the months that followed, growing tensions and conflicts, largely along ethnic lines, have resulted in significant displacement and a breakdown in law and order across much of the country, threatening progress on key reforms.

This week we will publish a series of assessments of Prime Minister Abiy’s first year in office, looking at his government’s performance regarding eight key human rights priorities and providing recommendations on what more needs to be done in his second year in office, leading up to elections scheduled for May 2020.

Today, in Part 2 of 8, we look at the government’s performance on Freedom of Expression, including media freedoms.

Freedom of Expression

Significant progress has been made on media freedom in Ethiopia. In one year, Ethiopia has gone from being one of the leading jailors of journalists in Africa to having no journalists in jail for the first time since 2004. Diaspora media outlets previously banned in Ethiopia operate freely and journalists report few threats from the government’s security services. Despite the progress, there’s still a reluctance in the media to critique the government or ask difficult questions. Hate speech on social media, especially Facebook, is a serious and growing problem, although the government’s proposed hate speech law raises concerns it may be used to stifle legitimate expressions of dissent.

Background

Ethiopia’s government has a long track history of curtailing independent media, limiting the rights to freedom of expression and access to information. The media landscape has traditionally been heavily state-controlled and dominated by Amharic-language publications and broadcasts focused on events and issues in the capital, Addis Ababa. Since 2005, the government has shut down dozens of publications. Many journalists have been threatened, intimidated, and targeted for politically-motivated prosecutions under criminal or terrorism charges. As a result, at least 60 journalists have fled into exile since 2010. In 2017, Ethiopia was among Africa’s leading jailer of journalists. Self-censorship is common.

The government had also sought to suppress independent diaspora-led media outlets based outside of Ethiopia. Many blogs and websites run by Ethiopians in the diaspora were blocked inside Ethiopia. The government pressured satellite companies to drop the US-based Oromia Media Network (OMN), which disseminated independent information during the protests that began in 2015. The government arrested people who showed OMN in their businesses, jammed satellite television programs, and charged OMN under the country’s sweeping antiterrorism law in October 2016. US-based Ethiopian Satellite Television (ESAT) was subject to similar tactics. Radio stations broadcasting content in Ethiopian languages were also jammed, including Voice of America and Deutsche Welle. Internet shutdowns were commonplace during the 2015-2018 protests, made easier because Ethiopia’s only internet service provider is owned by the government.

In addition to the Anti-Terrorism law, the 2011 Freedom of Mass Media and Information Proclamation and the 2016 Computer Crime Proclamation have laid the legal groundwork for the government’s restriction of freedom of expression. The media law grants broad powers to initiate defamation suits and demand corrections in print publications, along with sweeping powers to deny media licenses. The criminal code also has criminal defamation provisions. The computer crime law has broad provisions that could be used to stifle critical commentary and freedom of expression. The law criminalizes defamation, distribution of unsolicited content, and content that “incites fear, violence, chaos or conflict.”

Individuals providing information to international or diaspora-based journalists have reported arrests and harassment, sometimes based on intercepted phone calls.

Under Abiy

In June 2018, the Abiy government unblocked access to 264 websites, including blogs and news outlets, to allow for “a free flow of information.” OMN and ESAT were allowed back into the country, charges were dropped, and they are now operating without restriction. All journalists in detention were released. Presently, there are no reports of journalists in detention in Ethiopia – for the first time since 2004.

However, during a wave of protests in September, the government shut down the internet and mobile data in parts of the country where there were demonstrations, restricting access to information. The government also announced plans to pass a hate speech law in December. While hate speech is a serious problem amid growing ethnic tensions, especially on social media, the government should be careful not to undermine efforts to reform repressive laws by drafting a new hate speech law that could be used for the same kinds of abuse.

State run television, while now reporting regularly on human rights abuses committed prior to the formation of Abiy’s government, rarely strays from government perspective. They have broadcast documentaries about alleged corruption and human rights abuses by previous government officials around the same time as these individuals were charged. The use of state television documentaries has been used in the past to undermine defendants’ right to a fair trial by mobilizing the public to support a judiciary that was far from independent of state control.

Journalists have also reported being assaulted when covering sensitive issues. In February, two journalists working with Mereja TV, one of the web sites unblocked in June, were detained by regional police on the outskirts of Addis Ababa while reporting on the government’s demolition of homes and allegations of forced displacement. The journalists were allegedly asked to explain why they hadn’t told police they were traveling to the site and were subsequently released after an hour. Upon release, the journalists were attacked by a group of young men, and one was beaten with sticks in plain view of the police. No one was arrested in relation to the assault.

While the Freedom of Mass Media and Information Proclamation was one of the laws Abiy pledged to revise, a new draft of the law is not yet available.

In July, Abiy appointed new members to the boards of the Ethiopian Broadcasting Corporation and the Ethiopian Press Agency, including opposition members.

Some journalists have reported to Human Rights Watch that it remains difficult to criticize the Abiy government due to pressure from editors and peers.

When Human Rights Watch visited the country in February, people were speaking very openly about sensitive subjects in public spaces, cafes, and mini buses, which is a marked change from a country once consumed by fears of monitoring and surveillance. A press conference that Human Rights Watch participated in was attended by dozens of journalists, many from state media – something that would not have happened in the past.

What more can be done

The media law and computer crime law should be reformed to guarantee freedom of expression. While hate speech online is a problem, any potential hate speech law should not unduly limit freedom of expression. There are other approaches that should be considered first, including public education campaigns. Social media companies have a significant role to play in terms of content moderation and public education campaigns. Internet shutdowns should stop. Journalists need the protection of law enforcement when doing their jobs. More can be done to support the development of an independent media, especially outside of Addis Ababa and for languages other than Amharic.