(Geneva) – The United Nations Human Rights Council should extend the mandate of the Commission of Inquiry on Burundi during its ongoing session in Geneva, Human Rights Watch said today. The commission published its latest report on September 4, 2019.

Broad support for the investigative mechanism from member states would send a strong signal to Burundi’s ruling party, the National Council for the Defense of Democracy-Forces for the Defense of Democracy (CNDD-FDD), and the government that the world is closely monitoring the situation ahead of the country’s 2020 presidential and legislative elections.

“The Commission of Inquiry’s report confirms that grave and widespread human rights violations are persisting,” said Lewis Mudge, Central Africa director at Human Rights Watch. “Despite these findings, Burundian authorities minimize and deny the gravity of the situation and have stepped up pressure on refugees to return.”

The commission concluded in its report that “serious human rights violations – including crimes against humanity – have continued to take place since May 2018, in particular violations of the right to life, arbitrary arrest and detention, torture and other forms of ill-treatment, sexual violence, and violations of economic and social rights, all in a general climate of impunity.” The targets, it said, were in particular real and suspected opposition supporters, as well as Burundians who have returned from abroad, including under a United Nations-backed voluntary repatriation program, and human rights defenders.

The commission was established in September 2016 to investigate human rights violations and abuses in Burundi since April 2015, and whether and to what extent they may constitute international crimes. Burundi’s government has refused access to the commission, and, despite evidence to the contrary, it claims the country is stable and peaceful.

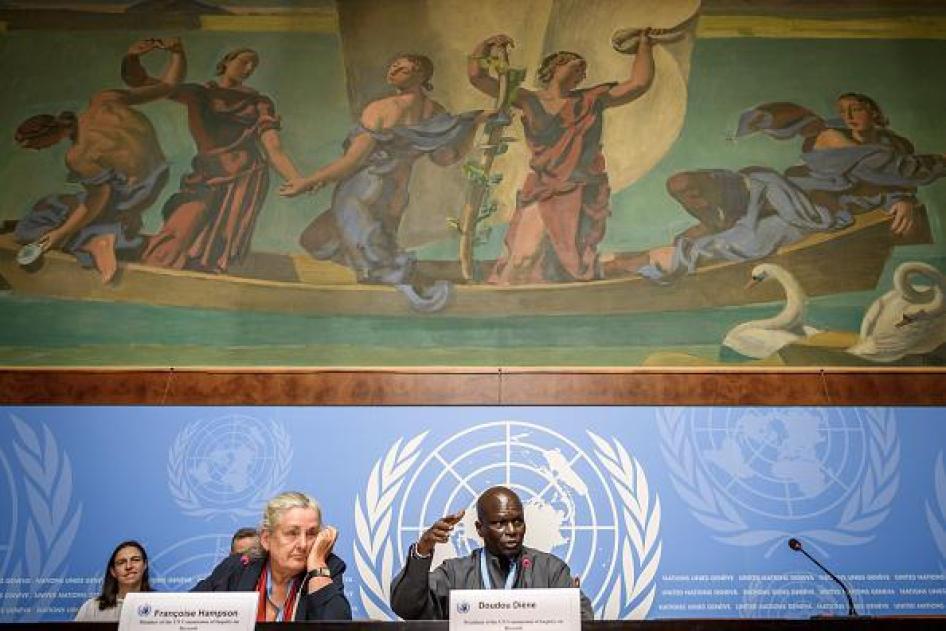

At a September 4 news conference, the commissioners described an environment of “‘calm’ based on terror.” Their report highlights that members of the ruling party’s youth league, the Imbonerakure, commit abuses against the population across the country and seek “to keep [them] in check and compel their allegiance to CNDD-FDD.” The commission documented cases of disappearances, sexual violence, torture, and ill treatment of Burundians who had recently returned from exile or been repatriated, and found that many repatriated refugees “had the food kits and the money they were given taken from them by Imbonerakure and local administrative authorities.”

On August 25, Interior Minister Pascal Barandagiye and his Tanzanian counterpart, Kangi Lugola, jointly visited Nduta camp in Tanzania and called on refugees to return to Burundi. Lugola later told Agence France-Presse that Tanzania would begin to send all Burundian refugees back on October 1 and continue at a rate of 2,000 a week, stating that “Burundi is at peace and the refugees should go home.” Just over 180,000 Burundian refugees currently live in three camps in Tanzania.

However, in a media statement, a UN refugee agency spokesperson said in late August that hundreds still flee Burundi each month and that conditions in the country are “not conducive to promote returns.” About 75,000 Burundians have returned from Tanzania since August 2017, when Burundi, Tanzania, and the UN refugee agency signed a tripartite agreement to assist those wishing to return on a voluntary basis. In March 2018, Burundi and Tanzania set a target of repatriating 2,000 Burundians a week for the rest of the year, a target that Lugola restated in August due to frustrations over a lower rate of return.

Setting targets for voluntary repatriation raises the risk of unlawful forced returns if fewer than the target figure sign up, Human Rights Watch said.

The 1951 Refugee Convention and the 1969 African Refugee Convention prohibit refoulement, the return of a refugee to a place where their life, physical integrity, or freedom would be threatened. Refoulement occurs not only when a refugee is directly rejected or expelled, but also when indirect pressure on individuals is so intense that it leads them to believe that they have no practical option but to return to a country where they face serious risk of harm.

Burundi plunged into a widespread political, human rights, and humanitarian crisis when President Pierre Nkurunziza announced his decision to run for a controversial third term in 2015. Abuses have persisted, and in June, Human Rights Watch published a report documenting worrying patterns of abuse, including killings, disappearances, arbitrary arrests, and beatings, mostly by the Imbonerakure and local authorities and targeting real or perceived members of the recently registered opposition party, the National Congress for Freedom (CNL, Congrès National pour la Liberté).

The commission is the last remaining monitoring mechanism that can publicly report on the human rights situation in Burundi. The government forced the UN rights office to leave the country in February, and most independent local nongovernmental organizations and media outlets have been shut down or suspended.

In September 2017, Burundi supported an alternative resolution proposed by African states at the Human Rights Council to provide technical support to the government to improve its human rights record. However, the government revoked the experts’ visas and expelled them in May 2018. Burundian authorities have also failed to sign a working agreement with African Union-mandated human rights observers, significantly hampering their work.

Extending the commission’s mandate will provide important scrutiny of the country’s grave human rights situation leading up to the May 2020 elections, Human Rights Watch said. Since the beginning of the year, the exiled independent organization Ligue Iteka has documented 264 killings, 573 arrests, 194 cases of torture, and 34 disappearances.

A May 2018 constitutional referendum, which paved the way for Nkurunziza to run for two new seven-year terms, took place in an environment of widespread ill-treatment by local authorities, the police, and Imbonerakure members, with authorities doing little to bring those responsible to account.

Although Nkurunziza has said he will not run again, the commission drew particular attention to the “major risk” posed by the 2020 election. Dozens of victims interviewed in 2019 told Human Rights Watch that refusing to join the CNDD-FDD and its youth league or to attend their rallies frequently resulted in threats and violent retribution.

A man who fled Ngozi province in June said that after refusing to join the ruling party on several occasions, he heard a knock on his door one night. “The CNDD FDD representative and two Imbonerakure from my hill were there,” he said. “They had arrested three men I know. They accused us of setting fire to a local party office, but it’s not true. They took us to a nearby river, and I saw one of the Imbonerakure lunge at one of the men with a machete. I jumped into the river and swam 50 meters to the other side.”

The man managed to escape the country. Human Rights Watch independently confirmed the deaths of two of the men he was detained with.

The political repression in Burundi has been compounded by growing concerns over the deteriorating humanitarian situation. According to the World Health Organization there have been over 5 million cases of malaria – almost half the population – and 1,800 malaria-related deaths in Burundi since the beginning of 2019. In its September report, the commission concludes that “the daily conditions of Burundians … are becoming worse and worse.”

“The victims deserve to see the people responsible for this crisis prosecuted, and the commission’s authoritative reports contribute to achieving justice,” Mudge said. “Those responsible for the ongoing serious crimes in Burundi want to shut the commission down because they know the world is watching and they will one day be held to account.”