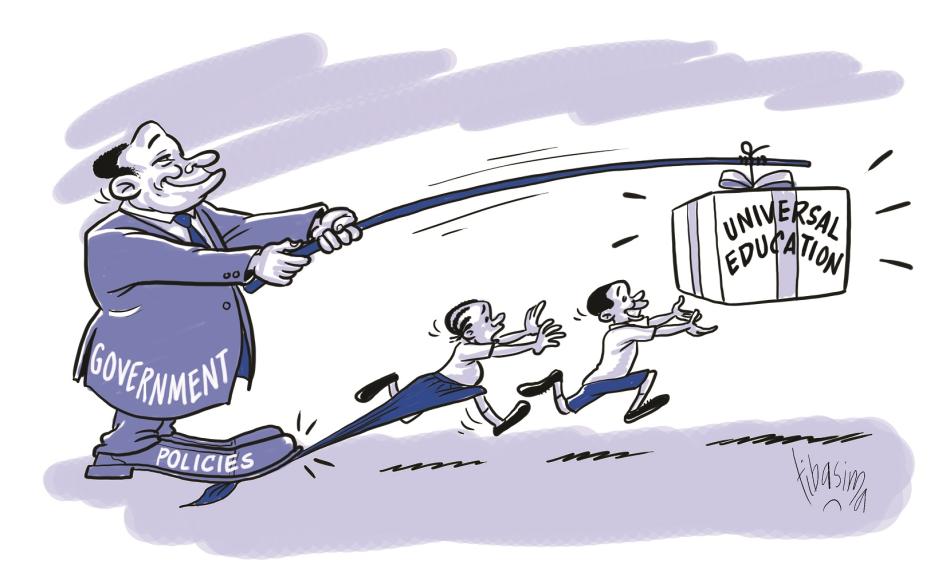

(London) – Governments should end all discrimination in children’s access to education and urgently strengthen policies and funding to ensure all children are able to benefit from their right to quality education, Human Rights Watch said today on the International Day of Education.

Governments have 10 years left to meet the United Nations' 2030 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which include commitments to guarantee that every child completes primary and secondary school, and is able to read and write. Governments have also committed to giving all children access to pre-primary education, and tackling discrimination against girls, women, and persons with disabilities.

“Many governments have been repeatedly warned that they are excluding large numbers of children from school because of their discriminatory practices and underinvestment,” Elin Martinez, senior children’s rights researcher said. “These governments still have time to reverse harmful approaches and do what is right for children.”

These human rights abuses, committed on a vast scale, perpetuate inequality and discrimination, deprive millions of children of education, hamper children’s experiences in schools, and have a multitude of negative social, public health, and economic effects on the countries where they occur.

Human Rights Watch research shows that many governments continue to implement policies that exclude large groups of children from public schools. Many governments also have not taken enough measures, or invested adequately, to ensure schools are safe, inclusive, and responsive to children’s learning needs.

These failures are compounded by the lack of monitoring to ensure governments are providing compulsory primary education to all children and identifying barriers forcing children out of secondary school.

Refugee children, children with disabilities, pregnant girls and adolescent mothers, and lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) children and youth, are often excluded from formal education, or suffer abuses while they’re in schools.

In many contexts, girls often face greater barriers to education than boys.

Children with disabilities continue to drop out of school because of lack of accommodation and many accessibility barriers. Millions of children do not complete compulsory primary or secondary school because of economic barriers, caused by school fees and indirect costs in many countries – even where ‘free’ education is a right under national law. Children continue to face widespread school-related sexual and gender-based violence, corporal punishment, and bullying. Schools are too often targeted or affected during conflict.

In 2019, Human Rights Watch documented Bangladesh’s unlawful policy of denying access to quality education to almost 400,000 Rohingya children by blocking them from attending public schools and stopping humanitarian actors from providing adequate education in refugee camps. Child refugees, particularly adolescents, from countries including Syria and Afghanistan, continue to face numerous barriers to formal education in Greece’s Aegean islands. In Jordan and Lebanon, fewer than 5 percent of refugee children complete their secondary education.

Tens of thousands of children and young adults with disabilities face ongoing discrimination and numerous barriers to access inclusive education. Human Rights Watch carried out research in Iran and Kazakhstan, where government-mandated bodies and medical tests can exclude children with disabilities from formal education. In Mozambique, children with albinism are still excluded from studying because of stigma and discrimination at school and in the community, as well as for fear of violence.

Conservative, unscientific, and abstinence-based approaches to sexuality education are harming children, particularly girls and LGBT children and youth, in countries like the Dominican Republic, which has the highest teen pregnancy rate in Latin America and the Caribbean, and South Korea, where LGBT-related materials are forbidden.

UN agencies have warned governments that they will fail to meet these goals unless they increase and target investment and retention programs for the most excluded and poorest children in their countries.

In recent years, some countries have made important progress in guaranteeing the right to education for groups of children that have been marginalized or excluded by their education systems. In Japan, the government adopted a new policy to prevent bullying of students based on their sexual orientation or gender identity. In Mozambique, the government revoked a policy that previously forced pregnant girls into night classes, leading to high drop-out rates among primary and secondary school students.

International and regional organizations, such as the UN and the African Union, should hold accountable governments that persistently deny education to large groups of children. Global education leaders and donors should publicly raise concerns with governments that commit human rights abuses in education, and ensure that funds do not directly or indirectly support the exclusion of children, or undermine international human rights obligations.

“Governments and international actors have a decade to meet this crucial deadline and show that they are committed to guaranteeing equal education for all,” Martinez said. “Education’s central role in sustainable development will only be unlocked when governments follow through on their promise to include, protect, and educate every child living in their countries.”