“Between the Fulani and us, there are no problems.” That is a refrain one commonly hears when in Burkina Faso. After all, the “country of honest men” - the meaning of Burkina Faso in Mooré, the land’s dominant language - has a long and proud history of peaceful intercommunal relations. But that did not stop members of an armed Burkinabe self-defense group – composed of Mossi and Foulse - from reportedly killing 43 Fulani villagers in Yatenga province on March 8.

The massacre is far from isolated and is most likely a result of the government’s policy of arming civilians in its fight against Islamist armed groups, a policy that threatens to further deepen existing ethnic tensions and to push more people into the ranks of these groups.

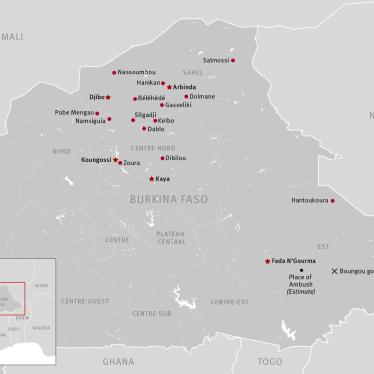

The country has faced a growing threat from Islamist armed groups since 2016, when they moved from Mali into Burkina Faso’s northern regions. They have progressively spread into the country’s eastern and now central regions, causing the displacement of 800,000 people.

Bidding on existing community fault lines and recriminations, the Islamist armed groups have concentrated their recruitment efforts on the semi-nomadic Fulani ethnic group. Since mid-2019, Islamist armed groups have ramped up their attacks on civilians, killing hundreds of people in poorly defended communities, often targeting victims on the basis of their ethnicity.

Those from agrarian communities including the Mossi, Foulse and Songhai have disproportionately suffered, leaving entire communities feeling terrorized by the attackers and dejected by the weak protection by their government. Between April and December 2019 alone, my organization, Human Rights Watch, documented more than 250 killings of civilians by the Islamist armed groups.

During a recent visit to Burkina Faso, I was able to confirm the details of three massacres over nine days in January, in the villages of Rofénèga, Nagraogo and Silgadji. Men on motorcycles wearing black garments and turbans shot and killed at least 90 men from the Mossi majority ethnic group in the town markets by. Survivors I met in Ouagadougou and Kaya told me the attackers, who they thought were members of armed Islamist groups, spoke Fulfulde - the Fulani mother tongue.

The rise in criminality that followed the fall of Blaise Compaoré’s 27-year rule in 2014, coupled with longstanding perceptions of impunity and the security forces’ corruption and deficiencies, has given rise to community anti-crime movements in recent years. When the interests of the community are threatened by looting or other crimes, groups of men gather, often along ethnic lines, to defend or avenge fellow villagers. The government has been trying to reconfigure, or repurpose, these groups to fight the Islamists.

The most prominent of the existing self-defense groups in Burkina Faso are the Koglweogo, or “guardians of the bush” in the Mossi’s Mooré language. Since their emergence in 2013, they have repeatedly been accused of abuses, including sequestration and torture of crime suspects.

In January 2019, they were accused of killing dozens of Fulani in the village of Yirgou, after suspected armed Islamists killed six people, including the village’s Mossi chief. More than a year later, the massacre remains largely unpunished, despite ongoing investigations.

On January 21, 2020, a day after the Nagraogo attack, which killed at least 36 mostly Mossi civilians, the 124 members of the National Assembly unanimously adopted a vaguely worded law creating Volunteers for the Defense of the Homeland. President Roch Kaboré announced that he would put forward this law following a November 6, 2019 attack by armed Islamists on a mining convoy in the Est region that killed 39 people. The Council of Ministers approved it in December.

The law mandates volunteers, whom the state will reportedly train for two weeks and provide with firearms, to “contribute, occasionally through the use of arms, to the protection of people and goods of their village or zone of residence”– which in the current context may clash with those of neighboring villages or communities.

“Fourteen days of training won’t be sufficient,” a civil society organizer said. “The Defense and Security Forces get much more training, and they still commit abuses.”

Since 2017, Human Rights Watch has documented over 200 cases of extrajudicial killings by Burkinabe security forces. A local human rights group documented an additional 60. These abuses are rarely investigated and may have become the single most important factor pushing young Fulani men to join the Islamist armed groups.

Yet, seemingly to prevent abuses, the law puts the volunteers under military authority and obliges them to collaborate with defense and security forces.

The law is also vague on selection criteria and fails to include adequate vetting to ensure that no one with a record of violent crimes is prevented from receiving weapons from the government. Despite the defense minister’s assurance to the media that no one under age 18 will be allowed to join the Volunteers, the law leaves recruitment up to the approval of the local community, gathered in a general assembly.

It seems likely that ethnic minority groups perceived as supportive of the armed groups will be excluded from the volunteer forces. Barring more rigorous selection criteria by the state, the Volunteers may end up being mobilized on the basis of their ethnic affiliation – not unlike the at-times abusive Koglweogo.

As a cautionary tale, Burkina Faso’s government need look no farther than neighboring Mali, where ethnic Bambara and Dogon have killed hundreds of Fulani civilians in dozens of massacres in central Mali. The Malian government is now struggling to disarm these heavily armed groups, which are organized into quasi-military structures and are increasingly a law unto themselves.

The current reality of the Burkinabe intercommunal landscape gathers all the elements needed for it to similarly catch on fire. And by and large, it is President Kaboré’s government that holds the matches. Should it accelerate plans for the volunteer force without ensuring proper vetting, training and, crucially, accountability – the country is likely to see more and more atrocities, and more and more young Fulani being pushed into the ranks of the Islamist armed groups.

But it is still possible to walk back from this edge, notably by improving the armed forces’ ability to protect civilians and by holding members of the security forces, self-defense groups and Islamist armed groups to account for abuse. Friends of Burkina Faso, France included, should make that clear to the government before it is too late.

..

Jonathan Pedneault is a crisis and conflict researcher at Human Rights Watch,