Criminal gangs have kidnapped for ransom at least 170 people near the Virunga National Park in the Democratic Republic of Congo between April 2017 and March 2020. Small groups armed with guns and machetes have beaten, tortured, and murdered hostages, raping women and girls, who make up more than half of them, while using threats to extort money from their families.

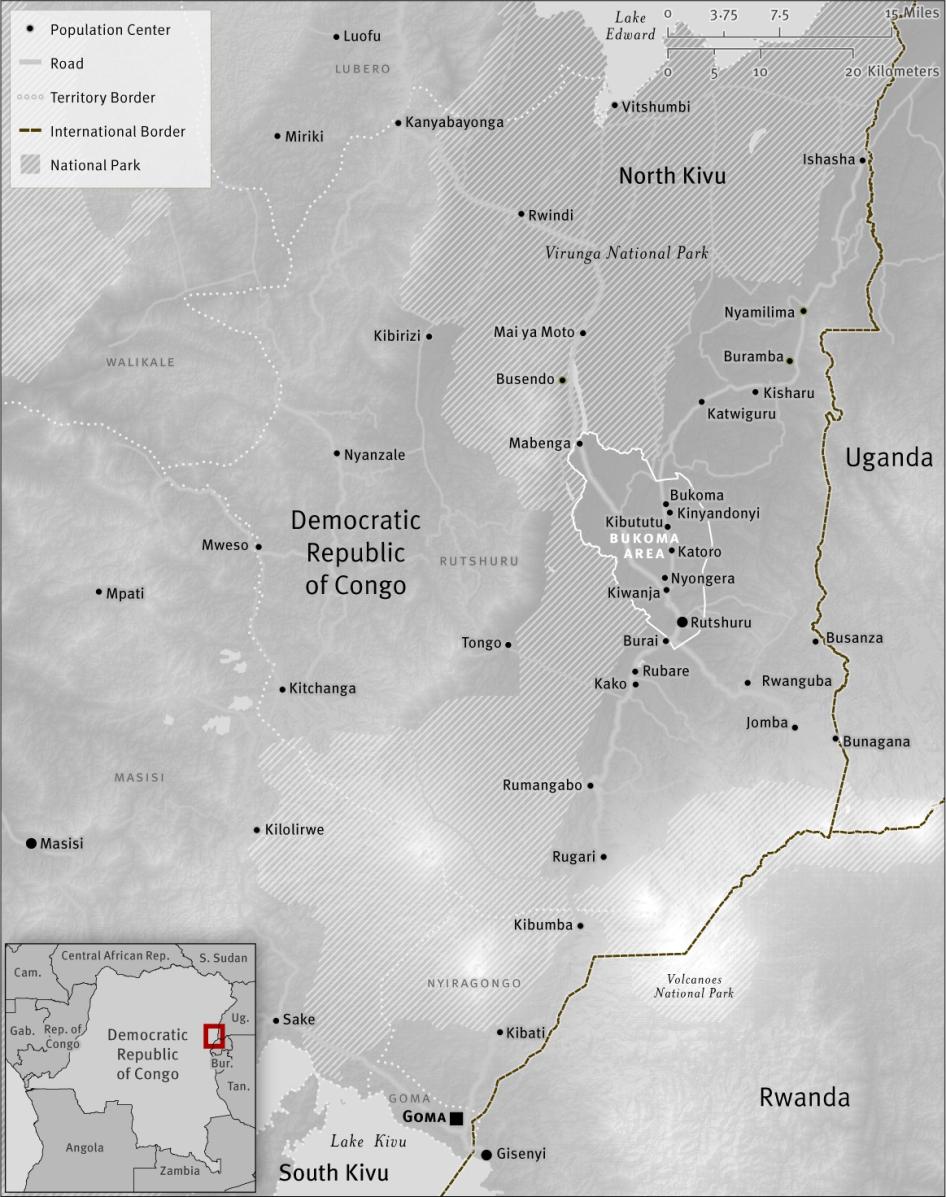

Congolese law enforcement should take steps to dismantle the criminal gangs and arrest those responsible for the kidnappings and sexual violence in the Bukoma area of Rutshuru territory in North Kivu province. The United Nations peacekeeping mission in Congo, MONUSCO, which has a field base within a 10-kilometer radius of the agricultural fields and areas where most kidnappings have occurred, should protect civilians by actively patrolling in high-risk areas, consistent with its mandate.

“Criminal gangs have demanded crippling ransoms from families and brutally raped scores of women and girls in Virunga National Park over the past three years,” said Thomas Fessy, senior Congo researcher at Human Rights Watch. “The Congolese government needs to end these gangs’ reign of terror while providing survivors – who face trauma and stigma – post-rape care and all the help they need.”

The Rwandan RUD-Urunana rebel group – a splinter faction of the Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda (FDLR) – controls much of the area around Bukoma. This armed group has been involved in abductions in recent years, and although the involvement of current or former fighters cannot be ruled out, Human Rights Watch has not established their involvement in these recent cases or whether they respond to a chain of command.

From December 2019 through June 2020, Human Rights Watch interviewed 37 people about the kidnappings, including 28 female survivors of sexual violence, 5 of whom were children at the time of the abuse. Human Rights Watch also interviewed local activists, government and park officials, and UN staff members.

Survivors said they were abducted, sometimes with their infants, while working in the fields or on the way home, near the town of Kiwanja. Their abductors would force them to walk, hands tied, for several hours into nearby Virunga National Park, which is a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Survivors said that the kidnappers would often tie men’s hands and feet and beat them. Women and girls said the captors methodically raped the female hostages, except prepubescent girls and older women. Many were also badly beaten. “The kidnappers told us that no woman would come out of there untouched,” said a 28-year-old survivor.

Survivors said their captors routinely insulted them, and threatened to kill them, including when talking by phone to their families. The 28-year-old woman said the kidnappers showed her and other hostages two bodies of men whom they said had been clubbed to death when they tried to flee. Other survivors said they were subjected to mock executions and other forms of torture. “When [they] couldn’t reach my father on the phone, they put a rope around my neck and hanged me,” said another female survivor, 19. “I saw death up close that day.”

Victims said they were exposed to rain and cold nights as they were held in the open for about 1 week to 10 days. They were barely fed or given poor-quality food. Most were released only when relatives paid a ransom ranging from US$200 to $600. The payments often caused severe financial hardship for families forced to sell land, leaving them with no source of income.

Women and girls were often raped multiple times a day and sometimes by multiple men. Only a few among the oldest and the youngest were spared. “We became [their] sexual objects, it never stopped,” said a survivor.

Victims and families who sought help from the police said they did nothing to find those responsible. In some cases, relatives did not report the kidnappings because they believed they would get no assistance or that it could even make matters worse. Longstanding impunity for sexual violence in the country as well as a largely dysfunctional justice system leave survivors with little recourse for justice, Human Rights Watch said.

“Rapes are motivated by economic interests as criminals look for money,” Rutshuru territory’s administrator, Justin Mukanya, told Human Rights Watch.

The Congolese government should urgently act to end the rampant kidnapping and sexual abuse by criminal gangs near Virunga National Park. It should seek the assistance of MONUSCO to develop plans to protect communities and prevent kidnappings. Police, MONUSCO, and park rangers should increase their intelligence-sharing capacities and work closely with each other to investigate kidnappings, identify suspects, and bring them to justice.

The authorities should provide survivors of sexual violence with assistance to help rebuild their lives, including post-rape and other medical care, psychological and social support, legal assistance, and financial assistance, and should work with communities to end stigma and discrimination against survivors of sexual violence.

“Human Rights Watch is unaware of any judicial investigation into the armed gangs’ abuses near Virunga Park and there is little help for survivors,” Fessy said. “The Congolese security forces need to work closely with each other as well as with the UN and park guards to put a stop to the kidnappings and sexual violence.”

The Kidnappings: 2017 – 2020

Human Rights Watch documented the kidnapping for ransom of about 170 people in 23 separate incidents that occurred between 2017 and 2020 in and around the Bukoma area. The number of those kidnapped, as well as those raped, is most likely higher, given the limitations of the research.

The Kivu Security Tracker, a joint project of Human Rights Watch and the Congo Research Group, reported that armed assailants kidnapped at least 775 people since 2017 in Rutshuru territory alone, and 1,190 throughout North Kivu province. Thus far in 2020, the Kivu Security Tracker reported that at least 200 people have been abducted for ransom in the province.

In most reported cases, gangs of three to five men armed with guns and machetes abducted people in their fields or on the road. The kidnappers often initially pretended to be harmless, claiming to be soldiers or approaching their victims to ask for water. The kidnappers would release some people, such as young children and older people, who were given the kidnappers’ phone numbers, so that their families could contact and negotiate ransoms for those being held.

The gangs have detained hostages in Virunga National Park. Catherine, who like all survivors quoted here is identified by a pseudonym to protect her safety, said that on the day she was kidnapped, the abductors beat male hostages with sticks. The men then forced female hostages to lie on the ground and hit their backsides. “They told us this was just the beginning,” she said. Other victims said that some of the male hostages had to be taken to hospital once they were released because they were badly beaten; at least one man was nearly strangled until he fainted.

“There were times when they would switch off their phones to increase pressure on families because they were not happy with the ransom offer,” said Yolande, another survivor. “Male hostages were then beaten harder.” She said the ropes around their hands and feet were tightened to torture them. The kidnappers threatened to kill Yolande if she refused to have sex with them: “They showed us human skeletons and said they were people they killed after they disobeyed their orders.”

In October 2018, kidnappers executed a man shortly after he was abducted, said two witnesses. They said that he told them he had been taken twice before and, having already sold his plot and his field for previous ransoms, had nothing left to pay. “They shot him dead right in front of us – it was the scariest moment of my life,” said Yvette. “They then took each one of us, put them in front of the body, and asked how we were going to pay our own ransom.”

“[The kidnappers] said that, if anyone tried to run away, they’d catch them, cut off their head, and throw it into the river,” said Florence. She said that one hostage’s family was only able to gather $100 for the release of their relative and they were told it would only be enough to pay for “a tarpaulin, a can of lutuku [a traditional alcoholic beverage], and a few other things to organize his wake [implying that they would kill him unless a higher amount was paid].”

The kidnappers also threatened to beat or kill infants. Denise said that they threatened to beat her 7-month-old child each time he cried. “Even when [one of them] raped me, I had to do my best to get the baby to fall asleep first,” she said. Olivia said the kidnappers threatened to throw her child into the river because he cried too much. They also threatened to smash Louise’s 8-month-old against a tree.

The little food that was available was dirty and barely edible. “We barely ate anything – unwashed, peeled cassava, which we prepared with stagnant water,” said Marie. “We only ate at night because we were not allowed to light the fire during the day, to avoid being spotted.” Julie said the kidnappers sometimes cooked corn. “It was up to them to give us a portion or leave us hungry,” she said. “They would give us very little water, just a spoonful to drink; no more than that.”

Sanitary conditions were dire, and those held far from the river were not able to wash. Rachel and her child were held in a forest. “I would pick leaves from plants to wipe the loincloth that we were lying on when the baby defecated on it,” she said.

Elisabeth said she was asked to call her family to tell them her “last words before [she] was killed.” She was then forced to kneel, her hands tied behind her back. “I was shaking, I can still feel my fear,” she said. “They kept me tied up the whole day.” She was eventually released after her family paid $400.

Most kidnappers followed the same modus operandi and appeared to be in contact with each other, suggesting that the smaller groups were part of a broader linked enterprise. Victims said that the kidnappers, most of whom spoke Kinyarwanda, which is used in Masisi territory and in Rwanda, wore rags and rubber boots. Others spoke Kinyabwisha, a Kinyarwandan dialect spoken in Rutshuru, or Swahili. Former hostages said their kidnappers called each other by nicknames and knew the area well. At least three survivors had met one of their kidnappers before they were taken, and one survivor said she saw her abductors in Kiwanja two weeks after her release.

Local authorities in Bukoma confirmed to Human Rights Watch that joint MONUSCO-Congolese army patrols were conducted in the area. “But the number of soldiers and police officers deployed to deal with the insecurity in the area isn’t enough,” said the Bukoma chief, Modeste Kabori. Human Rights Watch shared its research findings with MONUSCO, which said in an email that “[Congolese troops] and ICCN [Congolese Institute for Nature Conservation] are primarily in charge of securing the Virunga National Park.” It added: “MONUSCO will enhance [patrol and assessment missions] and will also continue to advocate with the authorities to exert more efforts to better control the zone.” A team of over 700 park rangers also protects Virunga Park, covering 7,800 square kilometers, an area nearly the size of Cyprus. But park officials told Human Rights Watch that they do not have the capacity to provide protection everywhere, and that multiple areas of the park are under threat by armed groups.

Local vigilante groups have sprung up due to the absence of effective protection against the kidnappers, said victims and various other sources.

Human Rights Watch previously documented kidnappings that skyrocketed in Rutshuru in 2015. Then, the vast majority of victims were men. When women were captured, they were often robbed and immediately released.

Sexual Violence

In most of the cases reported to Human Rights Watch, the women and girls kidnapped were routinely and repeatedly raped, several times a day, and sometimes by several men. Their abductors often raped them next to male hostages, who remained bound. The rapes usually started on the first night. “They took us from the start, they didn’t let us breathe,” said Sophie. “Even in the rain, they had no mercy. During the rape, we would lie on the ground or in the mud.” Marie, 15, described the first night after she was kidnapped:

Each of [the kidnappers] took one girl into the forest. The one who took me asked me how old I was and if I went to school. He told me to take off my clothes and lie down on the ground; he had a grenade in his hand. When I screamed, he hit me and told me to be quiet. I was in a lot of pain and cried silently as he raped me.

Accounts from survivors suggest that inflicting harm through sexual violence, beatings, and death threats was part of the kidnappers’ strategy to obtain ransom payments rapidly. Olivia said: “When they raped us, they would tell us that if we didn’t pay up, they would keep us as wives, or that they would kill us.” Louise said:

They whipped us badly; five whips … we couldn’t even stand up afterward. We begged for mercy, but they forced us to have sex with them.… [A kidnapper] took his rifle and his machete. He placed himself between me and another hostage who was tied up and she was forced to watch while he raped me. If I moved, he would threaten to cut my head off with his machete. He would rape us like that every day.

Irene said a man who raped her was carrying a knife and a gun:

He put his gun to my head and said that if I tried to remove it, he would kill me with his knife. He said he wouldn’t shoot me because bullets are expensive. He told me that if he decided to kill me, he would cut me into little pieces, and I would have to eat my own flesh before I died. After that, he would do anything he wanted to me or take me anywhere with him. When I dared to cry, he would hit me in the head.

Sarah, 18, was 3 months pregnant when she was kidnapped. “[My abductors] would ring my family while they were raping me so my relatives could hear me scream; they wanted to make them feel how we were suffering to make sure they would pay up,” she said. Another survivor, Adele, said some girls “were constantly raped; it was relentless.... They always had to satisfy the insatiable desires of their torturers.”

Irene said the violence continued even after her ransom was paid. “[They] decided to make us suffer terribly one more time. They brutally raped us despite our wounds and the dirt on our bodies,” she said.

Physical and Psychological Trauma

The kidnappings have been life-altering for the women and girls Human Rights Watch interviewed, inflicting long-term trauma and harm. Yvette said she and other former hostages did not look like themselves after their ordeal. “Everyone who saw us was stunned.”

Many women and girls suffered lasting physical injuries and conditions. Some survivors went to health centers or hospitals shortly after their release, where they were given basic post-rape medical care, including medication to prevent sexually transmitted diseases and unwanted pregnancy. However, social and medical services are extremely limited in Rutshuru territory.

Some survivors described suffering vaginal damage or lasting abdominal or pelvic pain. Other symptoms survivors described included vertigo, high blood pressure, or other body pain, and some said they fall sick more frequently since they were kidnapped. Human Rights Watch spoke to two survivors who were pregnant when they were abducted and raped.

Psychosocial, or mental health, support is limited in Rutshuru territory. While some former hostages said they had received some initial psychosocial support through local health centers, others had been unable to get any psychosocial support.

Sexual violence survivors described mental health symptoms consistent with post-traumatic stress, including anxiety or panic attacks, frequent crying, hypervigilance, and nightmares. Denise said images of the rapes she endured often come back to her “like flashbacks.” Irene said: “When I fall asleep, I just dream about these scenes. When I’m in the fields, if a bird moves, I get scared thinking they’re still coming to get me.” Elisabeth said: “At home, everyone avoids sudden movements at my side. I’m still traumatized.”

Stigma and Rejection

Many survivors of sexual violence said that following their release, their husbands or partners had abandoned them or that family and community members had blamed or taunted them. “I find that I no longer have any value in society,” said Louise. Monique’s husband blames her for the ransom he had to pay: “When I just ask for some salt, he replies that all our money was spent [on the ransom].” Her husband also refuses to continue paying for her medical care, so she has had to treat herself with traditional medicine. “He asked me why I didn’t run away when I was captured,” she said. “But how could I do that with a child on my back?”

Irene’s husband sometimes tells her to “go back to the ‘husbands’” she left where she was held. “He says he’s being laughed at everywhere, that these things hurt him,” she said. “He keeps saying that he’ll just go away to Uganda and leave me here.” Sarah said her husband has been threatening to leave her since the kidnapping: “He’s been insulting me, saying that I’m not a complete woman anymore. Our situation is bad. And the talk continues within the neighborhood. Many people say that they would not accept to live with a woman who has been raped.”

Financial Hardship

In most of the cases documented, ransom payments ranged between $200 and $600 per hostage. “There were different prices for each of us,” Jeanne said. “We were like cows.” The kidnappers would also demand chickens, phones, crates of beer, or cigarettes.

Victims and their families have had to sell their home plots, farmland, and goods, or take loans. Many former hostages are now scared to cultivate their fields. “Coming out of captivity feels like you’ve been poisoned,” said Sophie. “After this experience, you feel unable to go to the fields.” Elisabeth said:

My relatives sold our fields and [our last] goat. They also sold a bag of beans that we had at home. They took loans from a shop and the parish.... We’re suffering so much in Rutshuru. We would all go to Uganda if only we could go on foot. We have no choice but to go the fields to get food, but going in fear is difficult.

Some girls had to give up their studies because the ransom payment meant their family could not pay school fees anymore. “I dropped out of school because the amount paid for my release was exorbitant,” 18-year-old Catherine said. “[My father] refuses to pay for my school fees.”

Failure to Protect and Lack of Justice

Many former hostages said their relatives did not believe the Congolese authorities or police would assist them. “The civil authorities in Rutshuru are doing nothing about [the kidnappings]. Even if you go and inform them, they say nothing and do nothing,” said Yolande. Irene had little faith in the police: “You can inform the police that someone is being strangled somewhere nearby, they won’t budge. They would tell you: ‘These are your children, it’s your business.’” Most survivors said that the police never interviewed them once they were released.

Others said their relatives feared retaliation from the kidnappers if they sought help from the police. “No matter what time or place, if I hear one of their voices, I’d be able to recognize them,” said Elisabeth. “But even if you run into them and report them, they might be arrested and sent to jail, but they won’t stay there more than two days. They told us that if anyone dared to denounce them one day, they would do us a lot of harm when they get out of jail.” Other survivors said that identifying kidnappers would be difficult and presented an obstacle to justice. “I didn’t go to the police to report them, because there was no point in accusing people you don’t know,” Constance said.

In at least one case, in late 2019, the police allegedly arrested residents and stole the ransom that a family was putting together to free one of their relatives. Facing anger by the community, the police returned the money, but their actions delayed the payment to the kidnappers, who inflicted further abuse on the hostage as a result. Grace, who was among this group of hostages, said that as a result the kidnappers struck a man in the head with a machete, badly injuring him.

The wave of kidnappings and lack of law enforcement response has driven men from the affected communities to form vigilante groups. Local activists have reported several incidents of mob justice. In November 2019, people armed with arrows and machetes killed three suspected kidnappers, also in the Bukoma area.

“Young men from the neighborhood were fed up with the problem and the absence of police action, so they decided to tackle the problem themselves,” said Grace. “They set up traps, captured three men they said were involved in the kidnappings, and burned them alive.” A local activist feared these vigilante groups might create more problems: “There’s a risk that they’ll use this to settle their personal conflicts or that they’ll do the same dirty work [as the criminal gangs].”