(The Hague) – The conviction of Dominic Ongwen on February 4, 2021 is a major step for justice for widespread atrocities committed by the brutal Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) in northern Uganda, Human Rights Watch said today. The guilty verdict at the International Criminal Court (ICC) shows that rights abusers can find themselves held to account even if years have passed since their crimes.

Ongwen is the first LRA leader to be tried before the ICC, and the first to be convicted for LRA crimes anywhere in the world.

The judges found that Ongwen was guilty of 61 counts of war crimes and crimes against humanity. The crimes include attacks on the civilian population, murder, torture, persecution, forced marriage, forced pregnancy, sexual slavery, enslavement, rape, pillage, destruction of property, and recruitment and use of children under the age of 15 to participate in the hostilities. The judges did not find evidence of duress or mental illness or defect that could negate his culpability for the crimes.

“The LRA terrorized the people of northern Uganda and its neighboring countries for more than two decades,” said Elise Keppler, associate international justice director at Human Rights Watch. “One LRA leader has at last been held to account at the ICC for the terrible abuses victims suffered. Would-be rights violators should take note that the law can catch up with them, even years later.”

Human Rights Watch issued a Question-and-Answer document and a feature article on the trial on January 27.

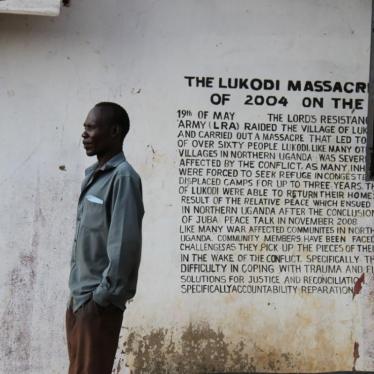

The LRA originated in 1987 in northern Uganda among communities in the Acholi region of the country, who suffered serious abuses at the hands of successive Ugandan governments. Their campaign initially had some popular backing, but support waned in the early 1990s as the LRA became increasingly violent against civilians.

The group, led by Joseph Kony, abducted and killed thousands of civilians and mutilated many others by cutting off their lips, ears, noses, hands, and feet.

The LRA’s brutality against children was particularly severe. Ongwen had been one such victim, as he was abducted into the LRA as a 10-year-old child in 1990. The ICC does not have jurisdiction over crimes committed by anyone under 18, but Ongwen was tried for crimes he committed as an adult. His abduction as a young child and the brutality he may have experienced should be considered as mitigating factors at his sentencing, Human Rights Watch said.

The LRA abducted over 30,000 boys and girls and forced them to become soldiers, laborers, and sex slaves. They were forced to beat or trample to death other children who attempted to escape and were repeatedly told they would be killed if they tried to run away. At the height of LRA activity in the early 2000s, as many as 40,000 children, known as the “night commuters,” each night fled their homes in the countryside to sleep in the relative safety of towns to avoid abduction.

Ongwen is the only LRA leader among five charged by the ICC who is in custody. Kony is an outstanding fugitive and the other three are declared to be or presumed dead.

Over four thousand victims were “participants” in Ongwen’s trial, separate from the role of witnesses. Early decisions in the case highlighted shortcomings, however, when it came to giving victims a voice in the choice of which lawyers would represent them. The ICC also actively conducted outreach to the local population on the trial. This included bringing community members to observe the trial at the ICC and audio and video screenings in northern Uganda of portions of the trial.

The ICC’s decision to open cases against Ongwen and other LRA leaders in 2005 coincided with a resumption of peace talks between the rebel group and the Ugandan government, although the final peace agreement was never concluded as Kony did not show up to sign it. Military campaigns against the LRA eventually pushed the group across the border into southern Sudan –now South Sudan and, in 2005 and 2006, into the Democratic Republic of Congo. The LRA later crossed in and out of the Central African Republic.

Starting in 2010, the US government provided assistance and military advisers to support regional efforts to arrest Kony and other LRA leaders, but in 2017 the US ended the program.

In recent years the LRA has splintered into smaller groups operating across central Africa. Kony and a group of his fighters are believed to be based in the Kafia Kingi, a disputed area on the border between Sudan and South Sudan. The organization Invisible Children, which tracks the various LRA groups, has documented continued abductions and looting.

Governments committed to justice for victims of LRA atrocities need to revisit how to ensure Kony’s ultimate arrest and surrender, Human Rights Watch said. The United Nations, African Union, and Economic Community of Central African States should support such efforts.

Following the verdict in the Ongwen case, the parties have 30 days to appeal. The ICC will also conduct hearings on sentencing and possible reparations for victims.

“Ongwen’s trial and conviction are major developments, but they should not obscure the need for Joseph Kony’s arrest and surrender,” Keppler said. “Countries should recommit themselves to seeing Joseph Kony face the ICC once and for all.”