(New York) – Indian authorities should immediately free all detained Myanmar asylum seekers, Human Rights Watch said today. The authorities should investigate the deaths of two women who had fled Myanmar and died in custody in Manipur state from Covid-19 in June 2021.

Since Myanmar’s military coup on February 1, tens of thousands of Myanmar nationals have fled the country to escape the violent crackdown. Approximately 16,000 Myanmar nationals have crossed into India in the four bordering states – Manipur, Mizoram, Nagaland, and Arunachal Pradesh, the media have reported. Those fleeing include parliament members, civil servants, military and police officials, and civil society and human rights activists. Most are in hiding, afraid of being arrested.

“People from Myanmar fleeing threats to their lives and liberty should be offered a safe haven in India, not detained and deprived of their rights,” said Meenakshi Ganguly, South Asia director at Human Rights Watch. “The Indian government should uphold its international legal obligations and work with the UN refugee agency to ensure prompt access to international protection mechanisms.”

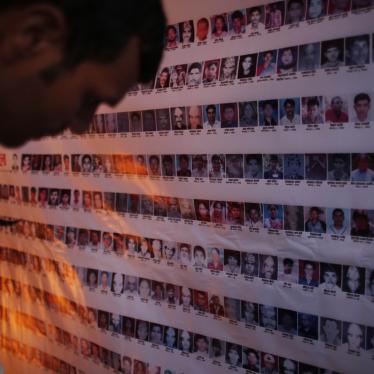

In June, two women from Myanmar, Ma Myint, 46, and Mukhai, 40, died from Covid-19 in a district hospital in Manipur state. Ma Myint and Mukhai were among 29 Myanmar nationals arrested on March 31 under the Foreigners Act for entering the country without valid travel documents. They were later placed in judicial custody by the district court. On July 2, the Manipur-based group Human Rights Alert wrote to the state human rights commission alleging that government officials were not providing immigration detainees with food and adequate health care, and that detainees were dependent on the charity of local civil society groups for food.

Ma Myint and Mukhai were only taken to a hospital once their illness was critical, according to Human Rights Alert and both died within three days of being admitted. At least 13 other asylum seekers also contracted Covid-19 in detention in Manipur.

Since February, the Myanmar junta and security forces have responded with increasing violence and repression to the nationwide anti-coup movement. Security forces have killed over 920 people and arbitrarily detained an estimated 5,300 activists, journalists, civil servants, and politicians. In March, the Indian government condemned the violence in Myanmar at the UN Security Council and called for the release of detained leaders, but at the same time the government ordered northeast border states to check the flow of “illegal immigrants from Myanmar.”

The chief minister of Mizoram state, which has had the greatest influx since February, wrote to Prime Minister Narendra Modi saying this directive was unacceptable and urged the national government to instead provide asylum to the refugees.

While Indian border guards have not pushed back any arrivals from Myanmar since the coup and several village councilors in northeast states have expressed a willingness to accommodate the refugees, the Modi government has provided no clarity regarding their status, local rights groups said. In addition, the office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) in India requires asylum seekers to travel to one of the agency’s designated centers, none of which are in the northeast, to apply for refugee status. As a result, thousands of Myanmar nationals in India fleeing persecution remain vulnerable to arrest, detention, and possible return to Myanmar.

UNHCR Detention Guidelines, which draw on international law, say that government authorities may detain adult asylum seekers only “as a last resort” as a strictly necessary and proportionate measure to achieve a legitimate legal purpose based on an individual assessment. Legitimate justifications for detention should be clearly defined in law, and conform to reasons clearly recognized in international law, such as concerns about danger to the public, a likelihood of absconding, or an inability to confirm an individual’s identity. Victims of torture and other serious physical, psychological, or sexual violence should, as a general rule, not be detained.

Refugees in the border states are largely dependent on civil society groups, who are providing support. Several groups have written to the national government asking it to provide humanitarian aid to the asylum seekers and ensure that specialized humanitarian agencies, including UNHCR, have unhindered access to them.

On May 3, the High Court of Manipur ordered safe passage for seven Myanmar nationals, including three journalists, to Delhi so that they could seek protection from UNHCR. “They fled the country of their origin under imminent threat to their lives and liberty,” the court stated, adding “They aspire for relief under International Conventions that were put in place to offer protection and rehabilitation to refugees/asylum seekers. In such a situation, insisting that they first answer for admitted violations of our domestic laws, as a condition precedent for seeking ‘refugee’ status, would be palpably inhuman.”

Although India is not a party to the 1951 UN Refugee Convention or its 1967 Protocol, the international legal principle of nonrefoulement is recognized as customary international law binding on all countries. Nonrefoulement prohibits countries from returning anyone to a country where they may face persecution, torture, or other serious harm.

Since 2017, Indian authorities have repeatedly sought to return ethnic Rohingya to Myanmar despite serious allegations of crimes against humanity and genocide by the military. In March, Indian authorities in Delhi, Jammu, and Kashmir detained dozens of Rohingya with plans to deport them to Myanmar. In April, the Supreme Court rejected a plea to stop their deportation.

Many of the detained Rohingya say they hold identity documents issued by UNHCR and that they feared for their safety in Myanmar. Over a million Rohingya have fled Myanmar, primarily to Bangladesh, most of them since the military’s campaign of ethnic cleansing that began in August 2017. The 600,000 Rohingya remaining in Myanmar’s Rakhine State face severe repression and violence, with no freedom of movement, no access to citizenship, or other basic rights. Abuses against the Rohingya in Rakhine State amount to the crimes against humanity of apartheid and persecution, Human Rights Watch said.

Indian authorities say that they will deport irregular immigrants from Myanmar if they do not hold valid travel documents required under the Foreigners Act. But any forcible returns to Myanmar would violate the principle of nonrefoulement.

India’s failure to provide fair asylum procedures or to allow UNHCR to make refugee determinations for those fleeing Myanmar because of the threat to their lives violates the government’s international legal obligations, Human Rights Watch said.

“Prime Minister Narendra Modi needs to ensure that the Indian government meets its obligations under international refugee law,” Ganguly said. “Indian authorities should treat those from Myanmar seeking refuge in India with dignity and provide them protection from further abuse.”