(Nairobi) – Kenyan authorities should amend measures requiring everyone seeking government services to be fully vaccinated to avoid undermining basic rights.

The proposed measures, announced less than a month ago, will go into effect on December 21, 2021. Given that approximately 10 percent of adults in Kenya had been vaccinated by the end of November, based on Health Ministry figures, the requirement risks violating the rights to work, health, education, and social security for millions of Kenyans.

“While the government has an obligation to protect its people from serious public health threats, the measures must be reasonable and proportional,” said Adi Radhakrishnan, Africa research fellow at Human Rights Watch. “Vaccination coverage hinges on availability and accessibility, and the government’s new measures could leave millions of Kenyans unable to get essential government services.”

On November 21 Kenya’s cabinet secretary for health, Mutahi Kagwe, announced that beginning December 21, authorities will require anyone seeking government services to provide proof of full Covid-19 vaccination. The services affected will include public transportation, education, immigration, hospitals, and prison visitation. Proof of vaccination will also be mandatory for entering national parks, hotels, and restaurants.

Kenya does not have a sufficient supply of Covid-19 vaccines to ensure that all adults can be vaccinated by the Health Ministry’s deadline, as a result of a lack of doses stemming from vaccine inequities and uneven global distribution.

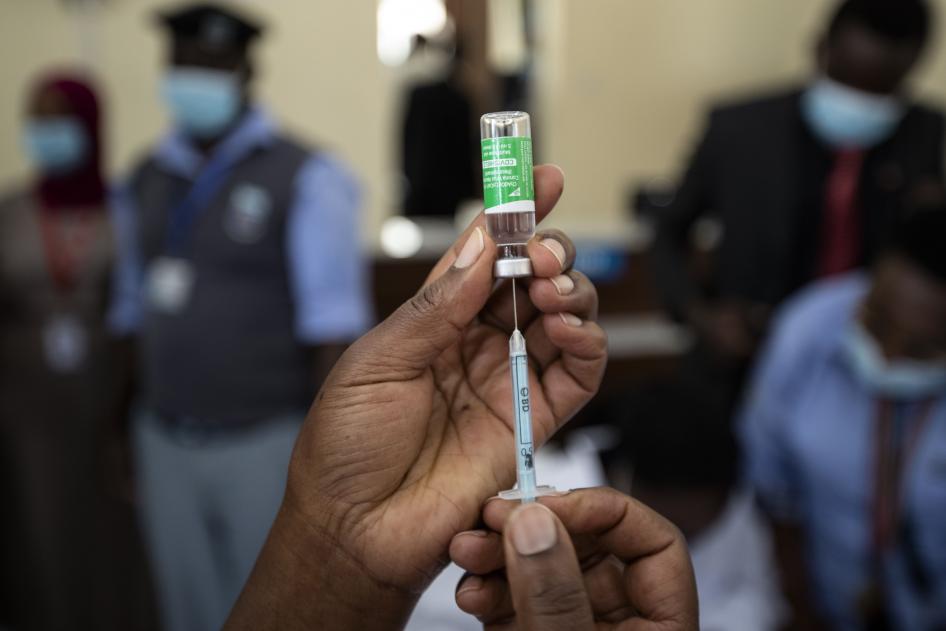

Kenya’s vaccination campaign began in March prioritizing health workers, teachers, security personnel, and people over the age of 58. Eligibility expanded to all adults starting in June. Currently, AstraZeneca, Moderna, Pfizer, Johnson & Johnson, and Sinopharm vaccines are available in Kenya. However, Health Ministry data indicates that there is a limited supply. Kenya, with an estimated adult population of 27.2 million and a total population of 55 million, has received approximately 23 million doses as of December 11 since the start of the vaccination program.

Kenya, like other low- and middle-income countries, especially in Africa, has struggled to access enough vaccines for their populations. More than 80 percent of the world’s vaccines have gone to G20 countries, whereas low-income nations have received just 0.6 percent of all vaccines, as the World Health Organization (WHO) reported. Kenya received just 1.02 million doses of the AstraZeneca vaccine in March to begin the vaccination program for its adult population of 27.2 million.

The vast majority of vaccines have not been distributed equitably throughout the world, as reported, due to concentration of manufacturing capacity in a few countries, and a refusal by the nations and pharmaceutical companies that developed the vaccine to share vaccine technology with other capable manufacturers and relevant WHO technology pools.

UN Human Rights experts, including the special rapporteur on the right to health, Dr. Tlaleng Mofokeng, criticized this vaccine hoarding behavior by wealthy nations. The experts stated that “there is no room for nationalism in fighting this pandemic. This pandemic, with its global scale and enormous human cost, requires a concerted, human-rights based, and courageous response from all States.” The experts also expressed concerns that some governments are trying to secure vaccines only for their citizens, which they said would be counterproductive to the goal of mass immunization.

The November 21 Kenyan vaccine requirement announcement does not provide details of how these new measures will be carried out and enforced nor does it provide alternative procedures for those who are ineligible for vaccinations or have a medical exemption, further risking arbitrary denial of access to services. When asked for additional details, Minister Kagwe stated “[a]s much as we will enforce these measures, accountability on implementing these measures will lie on individuals.”

Kenyan media have reported concerns among Kenyans about the government’s decision to issue its directive with just a one-month notice. According to a Frequently Asked Questions Guide on Covid-19 vaccinations published by the Health Ministry, the requirement to be considered fully vaccinated depends on the number of doses required for the type of vaccine used.

The majority of vaccines currently available in Kenya require two doses for full vaccination, with the second dose administered 4 to 12 weeks after the first, depending on the type of vaccine. So, it is likely that even people who get their first shot by the December 21 deadline will still face restrictions.

The Kenyan government has stated that the new policy aims to persuade more people to receive vaccines. “It’s becoming increasingly apparent that as countries battle the pandemic, a lot more emphasis is being placed on the need to have more and more people vaccinated,” Minister Kagwe said in the policy announcement.

Under international human rights law, the Kenyan government has a duty to ensure the right to health for everyone, without discrimination. It should promote vaccination by providing transparent information on the benefits and risks of the vaccine to a person’s health. Requiring proof of vaccination to access public services may act as a powerful incentive for people to get vaccinated, but the way it is carried out should also account for the numerous reasons that a person may not be able to receive the vaccine in time, Human Rights Watch said.

A reasonable vaccination requirement policy that is proportionate to the stated public health purpose should make accommodations so that unvaccinated people may still get essential services such as health care, without endangering themselves or others.

The Kenyan government’s human rights obligation to ensure that Covid-19 vaccines are available and accessible to everyone is severely undermined by the failure of high-income governments to collaborate globally and share technology to ramp up vaccine production. For over a year, efforts to promote equitable access to Covid-19 vaccines and therapeutics by waiving provisions of the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (“TRIPS”) have been blocked by high-income nations.

All governments have obligations to cooperate internationally, not to interfere with other countries’ ability to fulfill human rights obligations, and share the benefits of the scientific research they fund, Human Rights Watch said.

The Kenyan government also has an obligation to ensure that any restrictive policies or measures do not arbitrarily bar people from accessing essential services or from meeting their basic needs. The right to health includes an obligation to prevent and control epidemic disease, for which widespread vaccination is an important tool. But the right to health applies to everyone, regardless of their vaccination status. Vaccine mandate should be designed with careful attention to social, political, and economic barriers people may face; including vaccine availability and accessibility issues.

“Although vaccine mandates may be useful, they ought to be implemented within a broader public health strategy that emphasizes accessibility of vaccines and other preventive measures for Covid-19,” Radhakrishnan said. “A vaccine mandate should not arbitrarily create undue burdens for any population group, or disproportionately infringe on human rights.”