(New York) – Chinese government censorship seriously marred the 2022 Beijing Winter Olympics, which close on February 20, 2022, Human Rights Watch said today. The International Olympic Committee (IOC) and corporate sponsors have not spoken out about the government’s human rights record or used their leverage to press for rights improvements.

The Chinese government’s crimes against humanity targeting Uyghurs and other Turkic communities in Xinjiang have continued during the Games, as have serious violations in Hong Kong and elsewhere throughout China. In a news conference with the IOC on February 17, Chinese government official Yan Jiarong claimed that detention camps and forced labor in Xinjiang were “lies.” The IOC spokesman, Mark Adams, did not challenge Yan’s remarks but instead called the discussions surrounding Xinjiang “not particularly relevant to the press conference or the IOC.”

“The full spectrum of the Chinese government’s rights abuses continued throughout the Beijing Games, whether crimes against humanity in Xinjiang or censorship in the Olympic Village,” said Yaqiu Wang, senior China researcher at Human Rights Watch. “Through their silence, the IOC and its corporate partners have been complicit in Beijing’s efforts to ‘sportswash’ human rights violations before a global audience.”

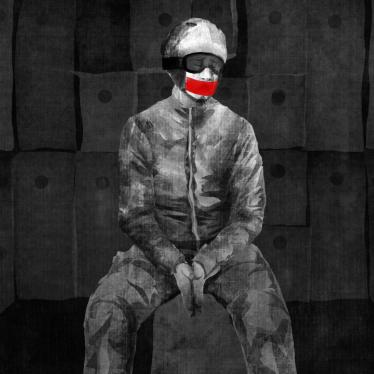

The Chinese government’s censorship apparatus intensified during the Olympics, Human Rights Watch said. During the opening ceremonies on February 4, Chinese authorities dragged away Dutch reporter Sjoerd den Daas as he was delivering a live report to the Dutch public broadcaster NOS. While the IOC claimed the incident was an “isolated event,” den Daas said that reporters had been “repeatedly obstructed or stopped by the police” while covering the Games. Finnish cross-country skier Katri Lylynpera said that Chinese officials asked her to delete photos she had posted on Instagram showing water flooding in an Olympic Village building. The Foreign Correspondents’ Club of China in its annual report released prior to the Games cited “unprecedented” challenges for reporting in and about the country.

Before the Games began, Chinese authorities warned athletes against “any behavior or speeches” that violated “Chinese laws and regulations.” The government has in the past routinely prosecuted Chinese citizens and occasionally foreigners for criticizing the authorities.

Germany’s luge gold medalist Natalie Geisenberger, who had criticized the Chinese government prior to the Games, recognized the risks to her safety and said she would only comment on China after leaving the country. Swedish gold medalist Nils van der Poel, upon returning home, said it’s “extremely irresponsible” to award the Games to “a country that violates human rights as blatantly as the Chinese regime is doing.” British-American skier Gus Kenworthy, while still in Beijing, expressed regret that his final Olympics was in a place he’d rather avoid: “I don’t think countries should be allowed to host the Games when they have things happening that are so egregious, and there are insane human rights atrocities happening.”

While the Uyghur skier Dinigeer Yilamujiang was chosen to light the Olympic Cauldron during the opening ceremony, she failed to appear before journalists after competing in an event even though IOC rules require all athletes to pass through a “mixed zone” where they can – but aren’t obliged to – answer journalists’ questions. Yilamujiang did not respond to any press inquiry from non-Chinese media, but gave an exclusive interview to the Chinese state broadcaster where she expressed gratitude for being entrusted with the role of torchbearer. The choice of a Uyghur was widely seen as the Chinese government’s rebuff of international criticism of its human rights violations in Xinjiang.

On the Chinese internet, censors took down a screenshot of a comment made by US-born Chinese gold medalist Eileen Gu on Instagram. In that post, Gu, who is immensely popular in China, asserted that a “virtual private network” (VPN) workaround for the Chinese internet is “literally free” in Apple’s App Store. The Chinese government in the past several years has ordered Apple to remove hundreds of VPNs from its App Store in China. Many netizens expressed anger over Gu’s comment, which they perceive as showing she is unaware of or exempted from the censorship facing ordinary Chinese. At the same time, Chinese state media outlets, including the People’s Daily and Xinhua, created many of the most popular social media hashtags about Gu.

Chinese authorities also censored content that was not overtly political but deemed damaging to their carefully curated image of the Olympics. During a livestream with the Chinese state broadcaster on February 10, Bing Dwen Dwen, the Beijing Games’ mascot, spoke in a deep male voice. The voice, which did not correspond to the cute, childlike look of the mascot, caused the dismay of many Chinese netizens. The hashtag “Bing Dwen Dwen has spoken” was subsequently removed from the social media platform Weibo. The clip was also quickly scrubbed off the Chinese internet.

Chinese authorities continued to stringently censor content regarding Olympian and tennis star Peng Shuai, who, in November, made a sexual assault allegation against former vice premier Zhang Gaoli. Peng’s situation remained so sensitive that the interpreter handling the Chinese translation of a pre-Games news conference did not mention her name when relaying a journalist’s question concerning her for IOC President Thomas Bach.

NBC, the exclusive United States broadcaster for the Games, faced criticism for not adequately reporting on human rights violations in the country or providing the political context in which the Games were unfolding. In response to a letter from Human Rights Watch in November, NBC said it stands “for press access and freedom globally” and would “resist any efforts to impede [its] access.”

The 13 TOP (The Olympic Partners) sponsors of the Olympics have remained silent on human rights issues pertaining to China and have not explained whether and how they have used their influence to address the government’s appalling human rights record.

The IOC also did not take adequate steps to ensure that the uniforms and other products it produced for the Games were free of links to grave rights violations in Xinjiang, Human Rights Watch said. An IOC statement describing human rights due diligence it conducted on suppliers was released only weeks before the Games began and contained significant gaps, including lack of analysis of suppliers’ responsible sourcing practices. Human Rights Watch and partner organizations wrote to the IOC on January 31 to request additional information about its sourcing practices but have not received a reply.

Since awarding the 2008 Summer Olympics to Beijing, the IOC has never used its leverage to press the Chinese government to respect human rights. There is no evidence that it challenged Chinese authorities’ threats to athletes before the 2022 Games, and instead helped whitewash Peng Shuai’s case and announced without caveats that Dinigeer Yilamujiang was “perfectly entitled” to be a torchbearer.

“The 2022 Winter Olympics helped cement the human rights violations the Chinese government first introduced during the 2008 Games,” Wang said. “This should be the end game for abusive Olympics hosts.”