Update: On September 10, 2022, the five defendants were sentenced to 19 months in prison.

(New York) – Hong Kong authorities should quash the sedition convictions of five people for publishing a children’s book series, Human Rights Watch said today. On September 7, 2022, the District Court found the authors guilty of “conspiring to print, publish, distribute or display seditious publications” under the Crimes Ordinance. They face up to two years in prison after a mitigation hearing scheduled for September 10.

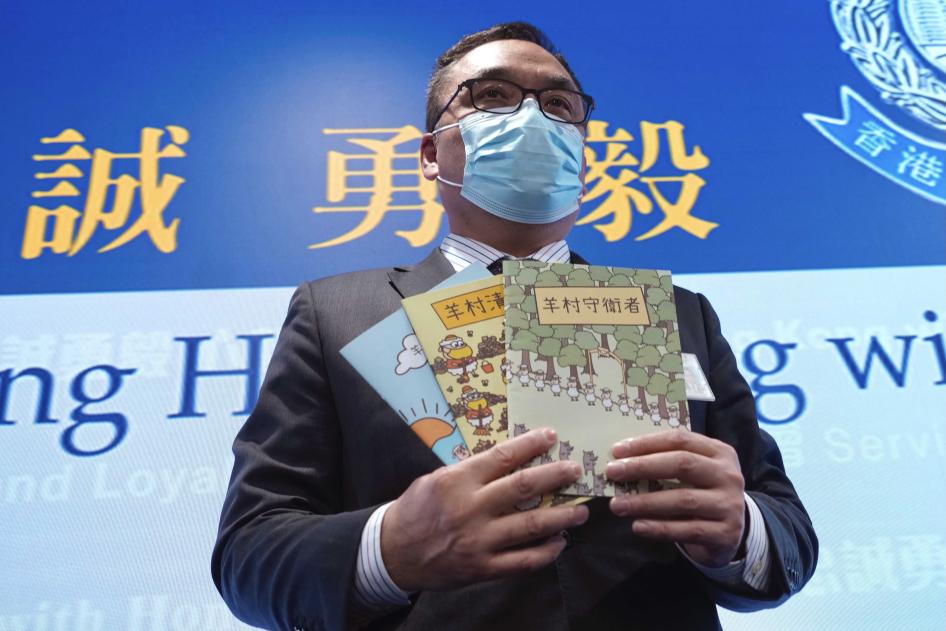

Prosecutors contended that the defendants’ three books, a series entitled Sheep Village about a flock of sheep resisting the tyrannical rule of a wolf pack, spread “separatist” ideas by portraying the Chinese government as a “brutal, authoritarian, surveillance state,” feared and worshipped by its people. They contended that the books were used to “unite anti-China and anti-Hong Kong forces.” The prosecution said without basis that such ideas could “weaken” the Chinese government’s sovereignty over Hong Kong.

“Hong Kong people used to read about the absurd prosecution of people in mainland China for writing political allegories, but this is now happening in Hong Kong,” said Maya Wang, senior China researcher at Human Rights Watch. “Hong Kong authorities should reverse this dramatic decline in freedoms and quash the convictions of the five children’s book authors.”

The five – Lorie Lai Ming-ling, Melody Yeung Yat-yee, Sidney Ng Hau-yi, Samuel Chan Yuen-sum, and Marco Fong Tsz-ho – ages 25 to 28, are speech therapists and executive committee members of the General Union of Hong Kong Speech Therapists, a pro-democracy labor union. In July and August 2021, Hong Kong national security police formally charged them with sedition. They were detained for nearly a year before being put on trial. In October 2021, the Hong Kong government removed the General Union from the registry of labor unions.

The Sheep Village books, published in 2020 and 2021, depict events that led to the 2019 protests in Hong Kong, raise awareness of the 12 Hong Kong activists held incommunicado in mainland China, and criticize the Hong Kong government for keeping open the borders with China at the beginning of the Covid-19 outbreak.

Since 2020, Hong Kong prosecutors have increasingly used the crime of “sedition” – an archaic, overly broad crime – to clamp down on peaceful dissent. The British colonial government introduced the Sedition Ordinance in 1938 and primarily used it against Chinese Communist Party supporters involved in the deadly 1967 riots in Hong Kong. Since then, and before the UK government transferred Hong Kong’s sovereignty to China in 1997, the colonial government had not used the sedition law, which it consolidated into the Crimes Ordinance in 1971.

Hong Kong authorities invoked the sedition law for the first time in July 2020, shortly after Beijing imposed the draconian National Security Law (NSL) on the city in June 2020. The Hong Kong government has charged 38 people and 4 media companies under the law. Those charged include journalists, academics, a radio show host, people who distributed pro-independence flyers, and those who clapped during the trial of a pro-democracy activist.

Although sedition is not a crime under the National Security Law, Hong Kong’s Court of Final Appeal ruled in December 2021 that it is an offense endangering national security. The court extended the National Security Law implementing rules to sedition cases, including sweeping police investigatory powers and a higher standard for bail. Following that court decision, sedition arrests jumped.

The Hong Kong government may have regularized the sedition law in its legal arsenal to penalize minor speech offenses, Human Rights Watch said. The law defines “seditious” in very broad terms and provides a low threshold for conviction, so long as the court is satisfied that a speech or publication intends to cause “hatred or contempt” against the government, “raise discontent,” or “promote feelings of ill-will” among Hong Kong residents.

The law also carries a shorter prison term than the National Security Law, which imposes a maximum of life in prison, allowing for a larger number of lower-level courts to handle these cases, rather than adding to the heavy caseload of political cases pending in the High Court.

Including the September 7 verdict, 13 people charged with sedition have gone through trials and all of them have either been convicted or pleaded guilty. In the first sedition sentencing in January, a man was jailed for eight months for putting up anti-government posters. In April, a pro-democracy activist, Tam Tak-chi, was sentenced to 40 months in prison for 7 counts of sedition and 3 counts of other offenses for chanting peaceful slogans. In July, a terminally ill, 75-year-old activist, Koo Sze-yiu, was given a nine-month jail term for painting phrases critical of the Chinese Communist Party on a prop coffin he had planned to use in protest of the 2022 Beijing Winter Olympics.

The Hong Kong authorities’ abuse of the sedition law has deepened the chilling effect across society since the National Security Law was imposed. In August, national security police arrested two administrators of the Facebook page “Civil Servants Secrets” on sedition grounds, days after its post showing a police officer asleep while on duty went viral. Following the arrest, at least five similar whistleblowing “Secrets” Facebook pages, including one for public hospital workers, were shut down without explanation.

The overly broad sedition law violates the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), which is incorporated into Hong Kong’s legal framework via the city’s de facto constitution, the Basic Law, and expressed in the Bill of Rights Ordinance. In its latest periodic report on Hong Kong, the United Nations Human Rights Committee said that the Hong Kong government should repeal the sedition law and refrain from using it. The United Kingdom repealed its own sedition law in 2009.

Concerned governments should speak out against Hong Kong’s abuse of the sedition law, Human Rights Watch said. The governments of Australia, the European Union, and the United Kingdom should impose coordinated targeted sanctions on officials responsible for violating the rights of people in Hong Kong, as the United States began doing in July 2020.

“The authorities have turned Hong Kong’s long-celebrated rule of law on its head to eliminate dissent,” Wang said. “Foreign governments should use every opportunity to raise the cost of committing these abuses.”