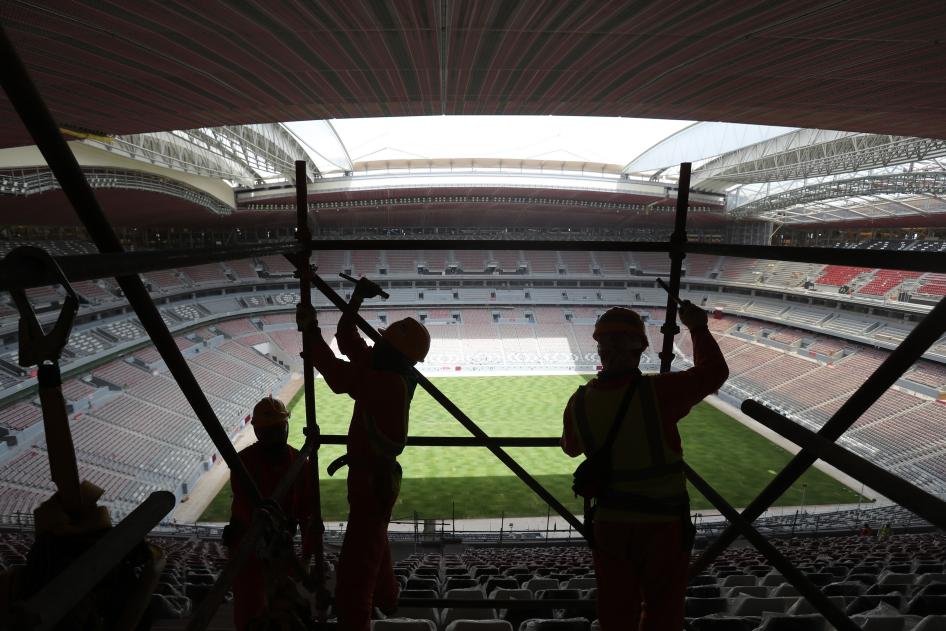

(Beirut) – FIFA and Qatar have failed in the past year to remedy abuses of migrant workers who made the 2022 Qatar World Cup possible, including families of thousands of migrant workers who died of unexplained causes, Human Rights Watch said today. The 2022 World Cup tournament may be over for much of the world, including FIFA, but the legacy of the tournament lingers on for victims in Qatar and across migrant origin countries.

“FIFA’s answer to addressing the terrible human rights legacy it left behind in Qatar should have been to provide remedy for migrant deaths and stolen wages,” said Michael Page, deputy Middle East director at Human Rights Watch. “By failing to do so, FIFA is showing disdain for the very workers who made the World Cup possible.”

Before the 2022 tournament, Qatari authorities and FIFA made grossly inaccurate and misleading claims that Qatar’s labor protection systems and compensation mechanisms were adequate to remedy these widespread abuses.

Human Rights Watch research has shown that Qatar’s labor reforms, made under intense global scrutiny, were extremely limited due to their late introduction, narrow scope, or poor enforcement, and that scores of migrant workers fell through the cracks. After the global spotlight on Qatar’s abuses dimmed, abused migrant workers and families of the deceased faced old and new forms of exploitation that Human Rights Watch documented in the post-2022 World Cup slowdown and that continue today.

FIFA’s irresponsible abandonment of migrant workers in Qatar and Qatar’s poor enforcement of reforms meant that many of the workers remain in Qatar in the post-tournament slowdown without work or pay and with outstanding wages and benefits contractually owed to them. Human Rights Watch documented that they are unable to return to their home countries as they fear that they would not be able to access the stolen wages and justice they are due from overseas.

A Qatar-based migrant worker said his company, dealing with a business slowdown, now is sending workers home for long, unpaid leaves. “The workers are given QAR 1000 [US$275] and airfare and told they will be contacted when there is work,” he said.

This leaves workers in a quandary, unable to quit as they are owed end-of-service benefits for over 10-15 years. These benefits add up to a significant amount that would go a long way back in their home countries. One worker said the extended leave policies leave workers without pay for months while the hope of future opportunities is dangled before them. The worker said that many migrant workers believe it is a way for companies to avoid paying end-of-service benefits.

Meanwhile, Qatar’s labor court has continued to be very slow in adjudicating outstanding cases brought by migrant workers who were cheated out of their wages or end-of-service benefits pre- and post-World Cup. Human Rights Watch has also spoken to workers who have been hesitant to file cases. “Even when the court rules in favor of workers … companies don’t obey court orders and pay workers what they are owed,” a worker said. “In this context, I don’t have the motivation to fight a legal battle.”

Some migrant workers have attempted to sue companies in jurisdictions outside Qatar. Forty Filipino migrant workers recently filed a lawsuit in the US state of Colorado against Jacobs Solutions Inc., a US firm that oversaw construction projects for four World Cup stadiums, for multiple alleged abuses, including unpaid wages, cramped living conditions, passport confiscation, and working in extreme heat. Fourteen of the Filipino workers worked for Al Jaber, a company in which, according to the lawsuit, Jacobs Solutions Inc. played a role “to monitor, direct, and control the labor supply chain.”

In an October statement to Quartz, Jacobs Solutions responded that they had not received or reviewed the lawsuit in detail, but emphasized their commitment to “respecting human rights and dignity.”

In 2022, Human Rights Watch reported that Al Jaber had hired workers under short-term project visas that forced them to return home before the end of their two-year contracts. The workers had paid exorbitant recruitment fees up to $1,570, but Al Jaber denied claims that workers paid recruitment fees in their response to Human Rights Watch.

In October 2023, two former Al Jaber workers told Human Rights Watch that the loans obtained to pay recruitment fees are still outstanding. One worker who was sent back after 10 months in Qatar said, “I do odd jobs now. My ten months in Qatar was a waste because I paid more than what I had earned.”

FIFA and Qatari authorities had an opportunity to address some of these bitter legacies by providing a remedy, including financial compensation, Human Rights Watch said. They could have built upon and expanded the limited successes of Qatar’s Workers’ Support Fund by reimbursing some migrant workers.

As one of the beneficiaries of the fund told Human Rights Watch, “When I got a call unexpectedly [from Qatar authorities] to come pick up my check [for unpaid wages] after months of following up, I could not believe it.” He immediately transferred the money to his family, who had taken loans for his children’s education and parents’ health bills.

Other limited positive examples in Qatar that addressed migrant worker abuses include the Universal Reimbursement Scheme by the Supreme Committee, the body responsible for planning and delivering World Cup infrastructure, under which workers were reimbursed for recruitment fees. Some companies adopted life insurance programs that compensated families of deceased migrant workers regardless of the cause or location of the worker’s death.

Unfortunately, only a handful of companies adopted such programs. For example, only 23 Supreme Committee companies adopted life insurance for their migrant workers.

FIFA and Qatar decided not to transform these small positive initiatives into a wider legacy of the 2022 World Cup for migrant workers. The call for remedy in the leadup to the tournament received strong global backing from football associations, sponsors, and politicians. In the months before the 2022 World Cup opened, FIFA indicated in a series of statements and briefings that it planned to compensate workers, such as at the Council of Europe hearing on labor rights in Qatar and to the Union of European Football Associations (UEFA) Working Group on Workers’ Rights in Qatar.

But on the eve of the 2022 tournament, FIFA President Gianni Infantino responded to remedy calls for workers by claiming that the Qatar Labor Ministry’s Workers Support and Insurance Fund would take care of compensation, which it has failed to do. Migrants’ realities of fighting for wages since the World Cup closed show that FIFA’s pledges were blatant falsehoods, and much of the abuses were predictable and preventable.

A son of a deceased Qatar-based construction worker told Human Rights Watch: “My father used to support the family financially, and now it is only me. My mother is getting older, and I have a newborn … expenses are rising. It is very difficult to take care of my family alone.”

FIFA appears to be repeating the serious errors it made during the 12-year preparation for the 2022 World Cup, Human Rights Watch said. FIFA has effectively awarded the 2034 World Cup to Saudi Arabia, a country that relies extensively on over 13.4 million migrant workers, many of whom come from the same countries as Qatar’s workers.

“Many families are left in the dark about what killed their loved ones or how to afford the next day’s meal,” Page said. “FIFA and Qatari authorities continue to deflect scrutiny from their abject failure of protecting workers rather than spending a modicum of effort to compensate the very workers who generated huge revenues for them.”