(内罗毕,2016年8月15日)-人权观察今天表示,在2016年7月,南苏丹政府军与反对派部队在首都朱巴冲突期间及其后,许多士兵杀害、强暴平民,并大肆劫掠平民财物,包括人道主义物资。政府军在多起案例中似乎刻意攻击非丁卡族(Dinka)平民。

由于使用枪枝与火炮进行无区别攻击,许多炮弹落在联合国基地内的境内流徙者营地,以及市内其他人口密集区,造成平民死伤。人权观察研究员曾在七月战事后访问朱巴,记录到多种犯罪行为,大多是隶属苏丹人民解放军(SPLA)的政府军士兵所为。

“南苏丹领导人们签署和平协议一年后,平民仍被屠戮,女性仍被强暴,数百万人仍不敢归乡,”人权观察非洲区主任丹尼尔・贝克勒(Daniel Bekele)说。“联合国已在8月12日决定増派维和部队前往朱巴,但打消了迟到已久的武器禁运。持续供应武器,只能为侵权行为火上浇油。”

人权观察表示,联合国及其成员国还应该针对严重侵害人权的人员实施制裁,包括资产冻结和旅游限制。非洲联盟委员会和捐助者们应当尽速准备成立混合法庭,调查并审判南苏丹自2013年12月爆发新战事以来──包括在近期战斗中──的最严重罪行。

根据一年前,2015年8月15日,签订的和平协议,双方同意合组全国统一政府、整合彼此部队、成立混合法庭及其他多项措施。根据协议,非洲联盟委员会应成立一个由南苏丹和其他非洲国家法官和工作人员组成的法庭。成立该法庭的关键步骤应在2016年10月前完成,但迄今尚未见到具体进展。

2016年7月8月,总统府召开内阁会议时,分别効忠丁卡族总统基尔(Salva Kiir)和努尔族(Nuer)第一副总统马扎尔(Riek Machar) 的部队突然交火。在这次激烈枪战之前数周,由于和平协议迟未落实,首都周围双方部队的摩擦已逐渐加剧。

双方部队在朱巴附近数个地点交战,为期四天。人权观察研究员在朱巴访问得知,士兵曾无区别开火,并炸射人口密集区或联合国基地内的流徙者营地,造成至少12名在联合国营地避难的平民死亡、数十人受伤。

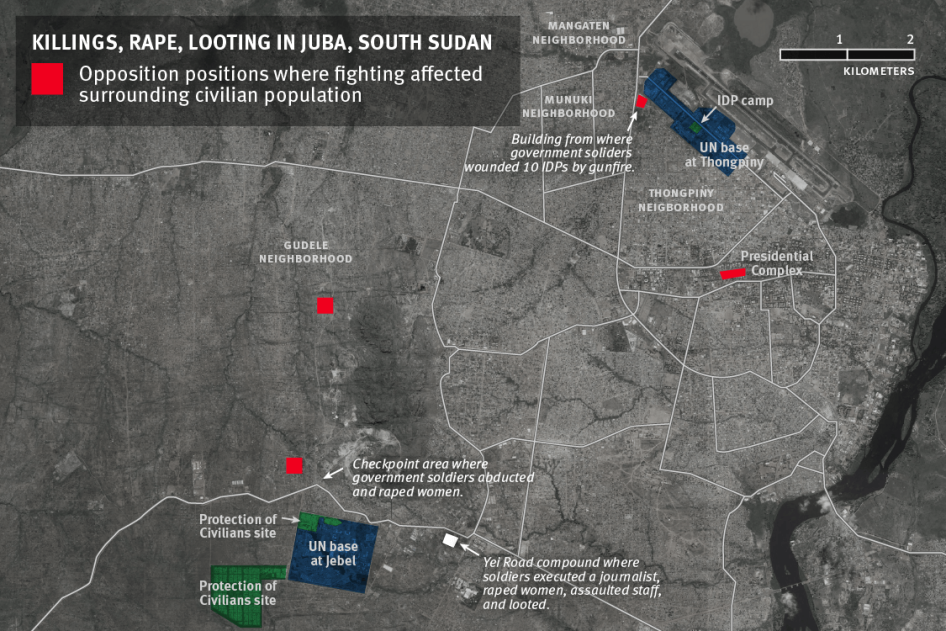

研究员并在朱巴多个地区记录到基于族群身分的杀人、强暴、轮暴、殴打、劫掠和骚扰。情况特别严重的地区包括:同平尼(Thongpiny)、蒙努基(Munuki)、曼葛登(Mangaten)、古德勒(Gudele)和杰贝尔(Jebel)。由于部分受影响地区受到安全管控,研究员无法全盘掌握侵权规模。犯下最多罪行的士兵,来自保罗・马隆(Paul Malong)将军和基尔总统负责指挥的部队。

人权观察也收到多项举报,指马扎尔部队,即南苏丹人民解放军─反对派(SPLA-in-Opposition,简称IO)涉及侵权,但未获独立验证。

据联合国统计,此次战斗至少造成平民73人死亡,36,000人在战斗期间或之后涌向联合国和救援组织营区寻求避难。朱巴市的战斗在7月11日停火后暂时平息,但政府军(SPLA)和反对派(IO)持续在朱巴外围和南苏丹其他地区交战。

某些案例中,政府军直接以特定族群为目标攻击平民。一名35岁男子说,7月11日停火前夕,他和其他27名努尔族男性躲在埃特拉巴拉(Atlabara)地区的比岱尔(Bedale)饭店,曾遭满载士兵的两台SPLA军卡包围:

士兵下来敲门,查问是否有努尔族人住在饭店。“我们央求门卫不要开门。士兵大喝:‘你们为何藏匿努尔人!’随即以重机枪扫射,把饭店大门和墙壁都打穿了。我朋友马丁就是这样被杀的。”

同一天,多名国际组织工作人员居住的一个小区,也遭到隶属政府军数个分队的大批士兵蹂躏。他们闯入后,处决了一名努尔族记者,强暴和轮暴数名女性,殴打和攻击数十名工作人员,并将整个小区翻箱倒柜洗劫一空。

7月11日停火后,士兵仍继续攻击平民,并触犯其他罪行。人权观察记录到多起政府军士兵趁女性冒险走出联合国基地平民保护营地(POC)寻找食物时加以拦阻,没收其物品并予强暴的案件。在数个案件中,研究员听说士兵曾提及被害人的族群身分,或怀疑她们支持IO叛军。联合国报导,在这次朱巴战斗期间及其后,反对派和政府军部队犯下的性暴力案件超过200起。

一名27岁妇女说,她在7月18日从城里带著食物返回POC时,遭到五名士兵拦下:“他们说:‘你是在给马扎尔运送子弹’,随即把我拉进一栋房子,但我不断挣扎。他们殴打我的头部和胸部,趁我疼痛难当将我强暴。我当时怀有两个月身孕,因为这件事就流产了。”

守卫联合国基地的维和部队兵员不足,无法保护在基地周边遭受性侵的女性。据媒体报导,7月17日有一名女性被士兵强行拉走,维和部队目击事件发生却未采取行动。若能加强巡逻或在重点区域增设岗哨,可以防止一部分强暴行为。7月18日,有一名援助工作者成功救回一名甫遭强暴的女性。

SPLA限制联合国南苏丹任务团(UNMISS)的行动,导致维和部队在战事期间只能待在基地。7月12日,该团要求政府安全部队解除限制,但维和部队又等了几天才获准移动和巡逻。人权观察表示,UNMISS既已允诺调查该团为何对性暴力见而不救,应当同时调查该团何以在战事爆发后对保护平民如此缺乏准备而成效不佳,并应解决问题,公布调查结果。

战事期间及其后,当民众试图逃难,政府军却在陆空两路管制迁徙,导致紧张和恐慌加剧。安全部队7月12日也在朱巴殴打一名反对派部长;7月16日,国安人员(NSS)拘捕了《朱巴监察者》(Juba Monitor )主编艾佛瑞德・塔班(Alfred Taban),只因他撰文批评交战双方,并呼吁基尔和马扎尔下台。他已于7月29日以健康理由获准取保候审。

8月12日,联合国安理会授权增派区域保护部队,该部队是UNMISS的一部分。这4,000名增援部队受命保护机场和其他关键设施,并得“交战任何预备攻击或参与攻击联合国保护平民设施、其他联合国建筑物、联合国人员、国际及国内人道工作者或平民的人员。”人权观察表示,加强保护平民应继续做为整个维和任务团的首要工作。

“南苏丹领导人有充分时间却未能终止对平民的侵权,既没有诚意约束侵权的部队,也无意确保麾下士兵罪行受到司法追究,”贝克勒说。“没有藉口继续拖延了:必须实施对高层领导人的制裁,以及武器禁运。联合国必须更有效保护平民,非洲联盟则应加速成立混合法庭。”

更多目击者和被害人提供的信息及陈述,请见后文。

Human Rights Watch researchers visited Juba between July 14 and 27 and interviewed more than 85 victims and witnesses of the recent violence, as well as aid and government officials. Researchers met with the South Sudan Human Rights Commission, the president’s spokesperson, and SPLA officials. Because of ongoing insecurity, researchers were unable to reach some of the neighborhoods most affected by the fighting but were able to interview residents who had fled the areas.

Tenuous Peace and Failed Security Arrangements

South Sudan’s current civil war began in December 2013 amid rumors that Vice President Machar was attempting a coup. Fighting and abuses quickly spread along ethnic lines.

Despite the August 2015 peace deal, fighting and abuses continued, including in previously peaceful parts of the country. The parties disagreed over a number of key issues, such as Kiir’s unilateral creation, in December 2015, of 28 new states and the government’s refusal to allocate cantonment sites for opposition fighters in parts of the country outside the greater Upper Nile region. The government submitted a number of reservations on several points of the agreement.

However, diplomats and the UN supported the deal. Machar returned to Juba on April 26, welcomed by hundreds of SPLA-in-Opposition (IO) fighters who had been ferried there on UN planes and by the Joint Monitoring and Evaluation Commission (JMEC), the international body in charge of monitoring the peace deal.

Both sides flouted the agreement from the start. Under the transitional security arrangements, the IO and government would respectively be allowed 1,470 and 3,420 soldiers in Juba, and would have to move all other forces 25 kilometers out of Juba. Yet as of early July, about 10,000 to 12,000 SPLA soldiers were estimated to be in Juba, many hiding in residential areas dressed as civilians, credible sources told Human Rights Watch. The opposition may also have received reinforcements from various sympathizers and fighters in and around Juba.

In addition, the parties agreed to position the IO bases close to civilian areas, including UNMISS headquarters and its protection of civilians (POC) sites. Locating a military base there clearly put the civilians at risk.

On July 2, government forces killed a senior opposition military intelligence officer, and on July 7, five SPLA soldiers were killed in a skirmish at a checkpoint. On the afternoon of July 8, a large-scale firefight between Kiir and Machar’s bodyguards in the presidential complex J-1 led to further clashes near the IO bases and the airport, which continued despite a lull on July 9, until a ceasefire on the evening of July 11.

On July 23, Kiir dismissed Machar and replaced him with another Nuer politician, Taban Deng Gai, despite objections from Machar and his allies. Fighting has continued in areas outside Juba and the fate of the peace deal is unclear.

Abuses against Civilians by Government Forces

Targeting of Non-Dinka

Many of the people Human Rights Watch interviewed said that government soldiers in various neighborhoods of Juba arbitrarily arrested, beat, and killed civilians and destroyed and looted property. Some civilian Nuer men said that uniformed Dinka security forces from either the army, police, or national security stopped them as they fled areas surrounding the presidential compound after the gun battle the evening of July 8, and demanded their identification cards, or spoke to them in Dinka to determine if they understood the language. Then the men tried to steal the Nuer men’s money and phones, sometimes attempting to kill them.

“When the incident happened at J-1, I was near Juba University with colleagues of mine,” said a man in his 30s. “I tried to run, but soldiers stopped me on the street and asked something in Dinka language. I was unable to answer. They said ‘Are you Nuer?’ in Arabic. I said yes and then they started to shoot me, I had seven bullets in my body. The soldiers left me for dead but I survived.”

Others were luckier. A journalist said: “When we heard the gunshots on July 8, I was at my office near the national security headquarters. As I tried to flee with colleagues, I was stopped by national security officers who asked me for my ID. I think they knew I was a Nuer. I was arguing with them when the car of a general pulled over and told them to leave me alone.”

On July 10, tanks and a large group of soldiers attacked and shelled the undefended house of the Shilluk king – a traditional leader who is not officially affiliated with either side – in the Munuki neighborhood.

“The tank shot three times towards our house, where we hosted about 100 Shilluk civilians, but missed,” a relative of the king said. “Then they used their heavy machine guns and started to spray bullets on the house. One of the rooms caught on fire. From inside the compound, I could hear them shout: ‘We need to destroy this house!’”

SPLA soldiers also targeted the house of Joseph Monytuel, the Bul Nuer governor of Bentiu – another non-Dinka government ally living in Munuki – where hundreds of Nuer civilians from the area had sought refuge. The governor’s bodyguards fended off the attackers a relative who fled to a UN base said.

In other areas known to be populated by non-Dinka such as Thongpiny and Mangaten, government forces on foot and in vehicles also attacked civilians, arrested men, and looted homes. Fighting and fear of abuses led at least 2,500 civilians to flee into a nearby UN base between July 8 and 12.

On the morning of July 10, in Thongpiny, soldiers killed a policeman and rounded up other men who looked or spoke Nuer. A 25-year-old Nuer woman who witnessed the events said: “They were deployed throughout my street. Some wore SPLA uniforms; others wore the fatigues of the Wildlife Guards. They killed a policeman in front of my eyes and I saw them arresting people who looked Nuer. They were putting them in the back of their pick-ups. When we saw this, we decided to flee.”

Another young displaced Nuer woman said that four Dinka soldiers forced their way into her family house in Thongpiny on July 10 and looted their belongings: “They put a gun to my head and asked: ‘Is your husband home?’ My husband was hiding under the bed but I said no. They said, ‘Whatever you have you give us, or we will kill you.’”

Some members of the security forces helped rescue civilians endangered by government troops. Witnesses, including staff at a nongovernmental group’s compound that was attacked, said national security officers rescued them from areas deemed unsafe, or from direct SPLA aggression. In one instance, national security officers hid about 40 Nuer in the office of Thomas Duoth, a senior Nuer officer commanding the NSS’ external security bureau.

Government forces also restricted the movement of non-Dinka men. As nongovernmental organizations and expatriates evacuated Juba following the ceasefire, authorities stopped non-Dinka men from leaving the country. On July 13, a Nuer worker for an organization had to pay a US$100 bribe to a security official to be allowed to enter the airport and was then refused permission to board the evacuation plane his organization had chartered.

“As I stood in the line for the customs, a national security officer pulled me aside and took my passport away,” he said. “He led me to the NSS’ airport office and there they took my name off the plane’s manifest. They would not explain why.”

Sexual Violence and Rape

Human Rights Watch found a clear pattern of rape against civilian women and girls by government soldiers during and after the fighting. Some government soldiers repeatedly gang raped or raped women and girls in areas surrounding the main UN base at Jebel, where the victims had taken shelter, during and after the fighting. In many of the cases, victims told Human Rights Watch that their attackers made statements suggested they were targeting the women for rape because of their ethnicity or presumed allegiance to Machar.

On August 4, the UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) reported that UNMISS had received reports of “widespread sexual violence, including rape and gang rape by soldiers in uniform and men in plain clothes,” and noted more than 200 alleged cases since July 8 at various locations in Juba, including near the UN House. The Office of the High Commissioner noted that both SLPA and IO soldiers raped women and girls.

Human Rights Watch also found evidence that government soldiers stationed in an area known as “Checkpoint” along the road to Yei raped dozens of women sheltering at a protection of civilians camp at the UN base at Jebel who ventured out of the camp in search of food – in some cases raping them just a few hundred meters away from the UN peacekeepers’ base.

“I was walking with a group of 10 women when soldiers in green uniforms and red berets stopped us,” a 20-year-old woman said. “They took phones and money from some, and then took four women away to a store and raped them.”

In other cases, soldiers transported women to compounds they occupied and raped them there. Two survivors in their twenties said that a group of several dozen soldiers stopped them in the checkpoint area on July 21, and beat, abducted, and raped them, along with a third woman. One said:

“They cut our clothes with knives. They beat us using rifle butts. They were talking about Riek Machar, they said things in Dinka language. Then they took us by car to another compound. They raped us there, in front of everybody. I’m sorry to say this, but this is what happened. They even raped her [the other survivor], who is pregnant,”

One 24-year-old woman said that government soldiers raped her on July 18 when she left the camp for town to look for food: “When I reached Checkpoint on my way back, there was a large group of soldiers who stopped me. Half of them wanted to rape me, the others wanted to kill me. Four of them raped me. Then they took my things and told me to go.”

Health authorities and aid groups should ensure that post-rape care for victims meets at least minimum standards, including post-exposure prophylactics to help prevent HIV infection, emergency contraception, and access to psychosocial services or other mental health care services.

Gang rapes in the Yei Road Compound

On July 11, fighting moved toward Jebel, where SPLA soldiers fought to capture the IO base near UN House. That afternoon, a large number of government forces attacked the Yei Road compound, which housed about 50 employees of several international organizations.

Witnesses said the soldiers arrived around 3 p.m., divided into groups, and immediately began breaking into structures, looting supplies, and entering residential areas and an apartment building, where they killed a prominent journalist, raped or gang raped several international and national staff of organizations, and destroyed, and extensively looted property.

They killed the journalist, 32-year-old John Gatluak, in front of the apartments, presumably because of his Nuer ethnicity, visible from his scarification. Witnesses said that the soldiers shot him in front of his colleagues, at close range. His body was seen lying face up, hands above his head, as if in surrender.

The soldiers also raped or gang raped several foreign women. “He told me I had to have sex with him or else I would have to have sex with all the other soldiers – so I didn’t have a choice,” said one survivor of multiple rapes. Another woman said: “He beat me and ordered me to take off my pants,” then raped her in front of other people.

Some witnesses said soldiers cheered as they took turns raping a woman or two women in a room. Soldiers often threatened the women with death if they did not comply. In one case of attempted rape, a soldier beat the woman with the butt of his gun, then another shot a bullet next to her head.

During the first day of the attack, which lasted until about 7 p.m., soldiers also beat many of the compound residents, sometimes demanding to know their nationalities or affiliations, broke into apartments, destroyed property and looted goods including satellite dishes, televisions, money, clothes, food, computers, and alcohol.

Many residents were not rescued for several hours, despite repeated calls to various organizations and security forces. During and after the rescues, the soldiers continued to ransack and loot the compound leaving nothing intact. Gatluak’s body was not retrieved for several days.

Other Looting

Starting after the ceasefire, large groups of government soldiers stationed near UN House, later joined by Dinka civilians looted the entire contents of the World Food Program (WFP) and the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) warehouses located in the vicinity, witnesses said. At the WFP warehouse alone, they stole 4,500 metric tons of food – enough to feed 220,000 people – as well as generators, air-conditioning, and other equipment.

Soldiers also looted the markets at Jebel and “Checkpoint” in the hours following the ceasefire.

Indiscriminate Attacks in Densely Populated Areas

During the four-day fight, both forces used a variety of weapons, including mortars, rocket-propelled grenades and, in the case of government troops, helicopter gunships acquired from Ukraine equipped with unguided rockets, and battle tanks. Ukrainian contractors also maintain the helicopters in Juba. Both forces used artillery in densely populated areas and in close proximity to poorly fortified UN bases and civilian protection sites.

International humanitarian law prohibits the use of indiscriminate force in densely populated civilian areas as the risk of harm to civilians outweighs any anticipated military advantage gained from the attack.

Human Rights Watch researchers found evidence that fighters fired mortars and artillery at or over POC sites. The use of these weapons in such circumstances is at least reckless and probably indiscriminate. Witnesses and humanitarian sources told Human Rights Watch that at least five shells hit the POC site 1 at the main UN base in Jebel on July 11.

One shell hit and damaged a medical clinic run by the international non-governmental medical organization International Medical Corps (IMC) at the site. Another killed two Chinese peacekeepers and prompted the retreat of all UN police and soldiers from the outer fences of the site, causing residents to panic and flee. Shells also fell into the adjacent and larger POC site 3, where about 30,000 mostly Nuer displaced civilians were taking shelter.

At least a dozen civilians who had sought safety in the protection of civilians sites at the main UN base in Jebel died from the injuries caused by shooting at and shelling inside the camps. Many dozens more were wounded.

On July 10, a stray bullet killed a 10-year-old boy in site 3. “He was hiding inside the ditch with other people, and the bullet came,” his aunt said. “He was shot inside the camp, “A 3-year-old boy was also hit by a stray bullet well inside the site. “He was hiding under the bed when the bullet hit him,” his mother said. “He’s now in the hospital.”

Soldiers also fought around another UN base at Thongpiny, near Juba international airport. At least one shell also hit an impromptu POC site inside the UN base at Thongpiny on July 11. Although the UN had closed the site in December 2014, people started seeking refuge from the fighting there on July 8 and by July 11 about 2,500 were inside the base, mostly displaced Nuer and Shilluk.”

A 22-year-old displaced woman said she witnessed a shell explode in the Thongpiny UN base: “I saw so many people wounded, bleeding, they were taken to the hospital. I saw one woman injured in the back. Another person was hit on the head, one on the leg.”

Ten civilians, including six children, were also wounded well inside the displaced persons’ site at the UN base at Thongpiny by bullets shot on the morning of July 11 from a nearby building, under construction, that had been occupied by soldiers and changed hands over the course of the fighting. Human Rights Watch received reports that the building was under control of government forces at the time of the shootings.

While Human Rights Watch was unable to establish with certainty whether the soldiers shot at civilians intentionally, some civilians said government forces aimed at them, with no clear military target nearby. A 28-year-old woman who witnessed the incidents said the shooters could see them: “The soldiers were on the roof of the building 300 meters away and they could see us. They were shooting at us. There were no other soldiers for them to shoot at, just us.”

Government forces also used helicopter gunships armed with unguided rockets against opposition positions, and tanks in some densely populated neighborhoods such as Gudele and Jebel, near the IO bases, and in Thongpiny, Munuki, and Mangaten near the airport and known to host sizable Nuer and Shilluk populations. The use of tanks by government forces in densely populated civilian areas significantly endangered civilian lives and structures.

Although it’s not the only factor, the ability to purchase arms and ammunition as well as the maintenance of military equipment by other countries since the conflict began are enabling both sides to continue to commit abuses in South Sudan, Human Rights Watch said. An arms embargo should help reduce these ongoing and unlawful attacks on civilians.

UN Response

At the onset of the fighting, the army ordered UNMISS staff and peacekeepers to stay inside their bases. The mission stated that its peacekeepers were seriously hampered in protecting civilians inside and outside its bases as a result. Nevertheless, UNMISS responses to the fighting were often inadequate or delayed.

At the Thongpiny base, UNMISS peacekeepers took more than six hours to open their doors to civilians who had fled the violence on July 10. “We were many people hiding in the sewage canals outside to the base because they would not open the doors,” said a 25-year-old woman resident of Thongpiny. “I was dirty but I was so afraid of the sound of the guns.”

The peacekeepers did not venture out of the bases to protect civilians under imminent threat even after the ceasefire. On July 17 peacekeepers guarding a POC site did not intervene when SPLA soldiers meters away abducted a woman. Although rapes took place in their line of sight, they did not increase patrols for several days.

On July 11, UNMISS did not respond to direct calls for protection by aid workers at the Yei Road compound, a kilometer from their base, where Gatluak was killed and several women were raped or gang raped. Witnesses said the UN’s rapid response team abandoned their rescue mission after learning NSS would rescue the residents.

While the South Sudanese government has accepted the idea of a Regional Protection Force, as outlined in an August 5 communiqué of the Inter-Governmental Authority on Development group working on South Sudan, known as IGAD Plus, it is imperative for the mission to address existing concerns regarding the efficiency of its current troops. The UN Security Council authorized a Regional Protection Force on August 12, but increased numbers are unlikely to make the mission more effective on its own, without improvements in other areas.

Under the Status of Forces Agreement between UNMISS and the government, peacekeeping forces have a right to patrol and move throughout the country, as well as to use lethal force to protect civilians, regardless of whether they have prior SPLA or government approval. UNMISS has promised to investigate its response to sexual and gender-based violence during the recent crisis, but the UN needs to investigate and effectively identify the factors that are incapacitating their response to threats against civilians, limiting their operational effectiveness, and causing a crisis of faith in the mission.

The UN mission should also increase its public reporting of abuses including attacks on the UN and international agencies. The lack of public reporting on attacks against UNMISS bases and personnel may have contributed to more violations of the status of forces agreement and decreased the mission’s capacity to act on its mandate.

Hold Abusers Accountable

Those responsible for the abuses documented, including commanders, should be held to account, either through hybrid, international, or national prosecutions. More immediately, and with the objective of compelling leaders to bring abuses to an end, individual UN sanctions such as travel bans and asset freezes should be imposed on top civilian and military leaders.

The SPLA’s chain of command appears to be heavily divided along ethnic lines, with ethnic Dinka commanders in charge of most decisions. Nonetheless, the coordinated manner in which the SPLA was able to deploy helicopters and tanks indicates an efficient command structure, and the success of the ceasefire declared by chief of staff Paul Malong on July 11 also indicates that he is substantially in control and command of the numerous troops active on the ground.

Malong, as well as Kiir and Machar, who formally are the commanders-in-chief of their respective forces, should be among those investigated for their role in these abuses. Military and civilian leaders both bear responsibility to ensure that operations are conducted in a manner that limits risks to civilians. When military and civilian leaders decide to use poorly trained and undisciplined troops with a poor human rights record, they may bear a responsibility for abuses.

Government commanders may be responsible for knowingly deploying abusive soldiers. Human Rights Watch researchers found that some of the government soldiers deployed at “Checkpoint” and involved in rapes were from SPLA Division 4, which has been singled out by Human Rights Watch and UN reports for committing grave human rights abuses, including rapes, during a 2015 offensive in Unity state.

South Sudan’s government has publicly announced that it would investigate the recent events and, on July 29, the council of ministers announced a court martial to try suspected offenders. But the government has a dismal track record for ensuring justice for human rights abuses or fair, public processes, or effective mechanisms for civilians to file complaints. Researchers were told that commanders would be expected to report soldiers who had committed crimes. Twenty-four soldiers have been charged with random shooting and looting, a UN source reported. None were accused of rape or killing.

South Sudanese authorities should also cooperate with the African Union to create the hybrid court envisioned in the 2015 peace agreement, to investigate and try the most serious crimes since the start of the conflict.

Finally, the UN should impose more targeted sanctions on individuals. Members of the UN Security Council have in the past been urged to sanction Malong, Kiir, and Machar. The two top leaders have yet to be added to the list of those proposed for sanctioning. Malong and Johnson Olony – an IO commander – were proposed by the United States in September 2015 but Russia, Angola and China objected.